Lyceum Theatre

Londres - Angleterre

Construction: 1904

Topologie du théâtre

Nombre de salles actives: 1

Salle 1: (2107) 1904 - Actif

Accès

En métro: Covent Garden

En bus: 6, 9, 11, 13 and 15

Adresse: 21 Wellington Street, London, WC2E 7RQ

Evolution

Bâtiment: 1765. Concert and exhibition hall designed by James Paine / 1794. Building converted to theatre use / 1815. Rebuilt by architect Samuel Beazley / 1830. Theatre burnt down; again rebuilt by Beazley. Demolished 1904 / 1904. New theatre designed by Bertie Crewe / 1939. Theatre closed / 1945. Let to Mecca Ltd and opened as a dance hall / 1991-6. Restored by Apollo Leisure Group and reopened as a theatre / Statutorily Listed Historic Building: Grade II*

Nom:

Propriétaire(s)

Ambassador Theatre Group

Remarquable

Samuel Beazley’s Greco-Roman portico to Wellington Street / Interior of 1904 by Bertie Crewe

2107

1904 - Actif

Before the extensive demolitions at the beginning of the 20th century that cleared the way for the creation of Aldwych and Kingsway, two theatres seemed to watch each other from either side of Wellington Street. To the west, almost overlooking the approach to Waterloo Bridge, was the Lyceum; to the east was the Gaiety, built in 1868 and closed for demolition on 4 July 1903. Wellington Street, running between Tavistock Street and the Strand, was only a little over 30 years old when the Gaiety was built, being an extension of Bow Street, and the then Charles Street, to the river. The Lyceum now looks at the rear of the former Morning Post building of 1907, designed by Mewes and Davis and faced in Norwegian granite.

The Lyceum began life as an exhibition and concert hall within the grounds of Exeter House, Strand, designed by James Paine for the Incorporated Society of Artists In 1765. Paine was a prolific architect, probably better known for his country houses, such as Wardour Castle, Wiltshire, and his extensive rebuilding at Alnwick Castle, Northumberland. He designed brilliantly in the Palladlan manner, but faded from fashion as Robert Adam prospered With his reinterpretations of the style, introducing a wonderful array of previously unexplored details.

In 1794 the building was converted to theatre use by Its owner, Dr Samuel Arnold, but he was unable to obtain a licence to present drama, and it was very soon let by the New Circus. Some time before 1799 It became the Lyceum Theatre, now in the ownership of Dr Arnold’s son S. J. Arnold. Madame Tussaud held her first Londgn Waxworks Exhibition in the building In 1802, and plays were put on, but without any great success. In 1809 the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, was burnt down and the company decamped to the Lyceum during rebuilding works; this was good news for Samuel Arnold Jnr, in that he was able, following the company’s departure in 1812, to retain his theatre licence. In 1815 he renamed the building the Theatre Royal English Opera House, and in 1816 had it rebuilt by architect Samuel Beazley to present mainly opera. However, In 1830 it was Itself destroyed by fire, and Wellington Street was extended over the site. Beazley was commissioned to rebuild the theatre again, this time a little further to the west, and on 12 July 1834 it reopened as the Royal Lyceum and English Opera House. In 1856 it was taken over again, this time by the Covent Garden Theatre Company, whose building had burnt down.

The only architectural feature of Beazley’s theatre extant today Is the cream-painted stone Greco-Roman portico, but the building did survive Intact until 1903, when extensive alterations demanded by the London County Council made it cheaper to demolish the major part of the structure in 1904.

The Lyceum will always be associated with two of the greatest names In 19th-century theatre, Sir Henry Irving and Ellen Terry. Born John Henry Brodrlbb in Somerset In 1838, Irving was educated in London. He learnt his art travelling with provincial companies mainly in the north of England, and returned to London and the Queen’s Theatre, Long Acre, in 1867; here he met Ellen Terry. Pursuing his gift for playing theatre's less savoury characters, Irving first appeared at the Lyceum in January 1887, and became actor-manager in 1878. He immediately engaged Ellen Terry to play Ophelia to his Hamlet, and that partnership was to survive until the summer of 1902, when they parted company. They had toured America eight times, and in 1895 Irving had become the first actor to be knighted. He died in 1905, but Ellen Terry continued her career, and was created dame in 1925; she died in 1928.

By December 1904 a new theatre, designed by Bertie Crewe, who had been chief assistant firstly to Walter Emden and then to W. G. R. Sprague, had been built and was opened to present melodrama to the public. Never hugely successful, it closed In July 1939, ostensibly for redevelopment, though the London County Council had its own plans for the site. The fortuitous declaration of war meant that the building remained standing, albeit in a virtually derelict state, until 1945, when instead of the anticipated demolition it was let to Mecca Ltd and reopened as a dance hall. It was from here that the popular television show Come Dancing was produced, and live entertainment continued until 1991 when the theatre closed. Between 1991 and 1996 a programme of restoration was undertaken by the Apollo Leisure Group, and on 31 October 1996 the long-dormant building was reopened by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.

The grand entrance foyer and staircase rise up in shades of red and light brown to Crewe’s spectacular auditorium with Its exuberant rococo decoration - Its chunky cherubs and fruity swagging not enhanced, however, by the brown shades In which it is currently painted. Although much of the. fabric is new, the theatre pays an undoubted tribute to the Apollo Leisure Group and to their architects, , Halpern and Partners.

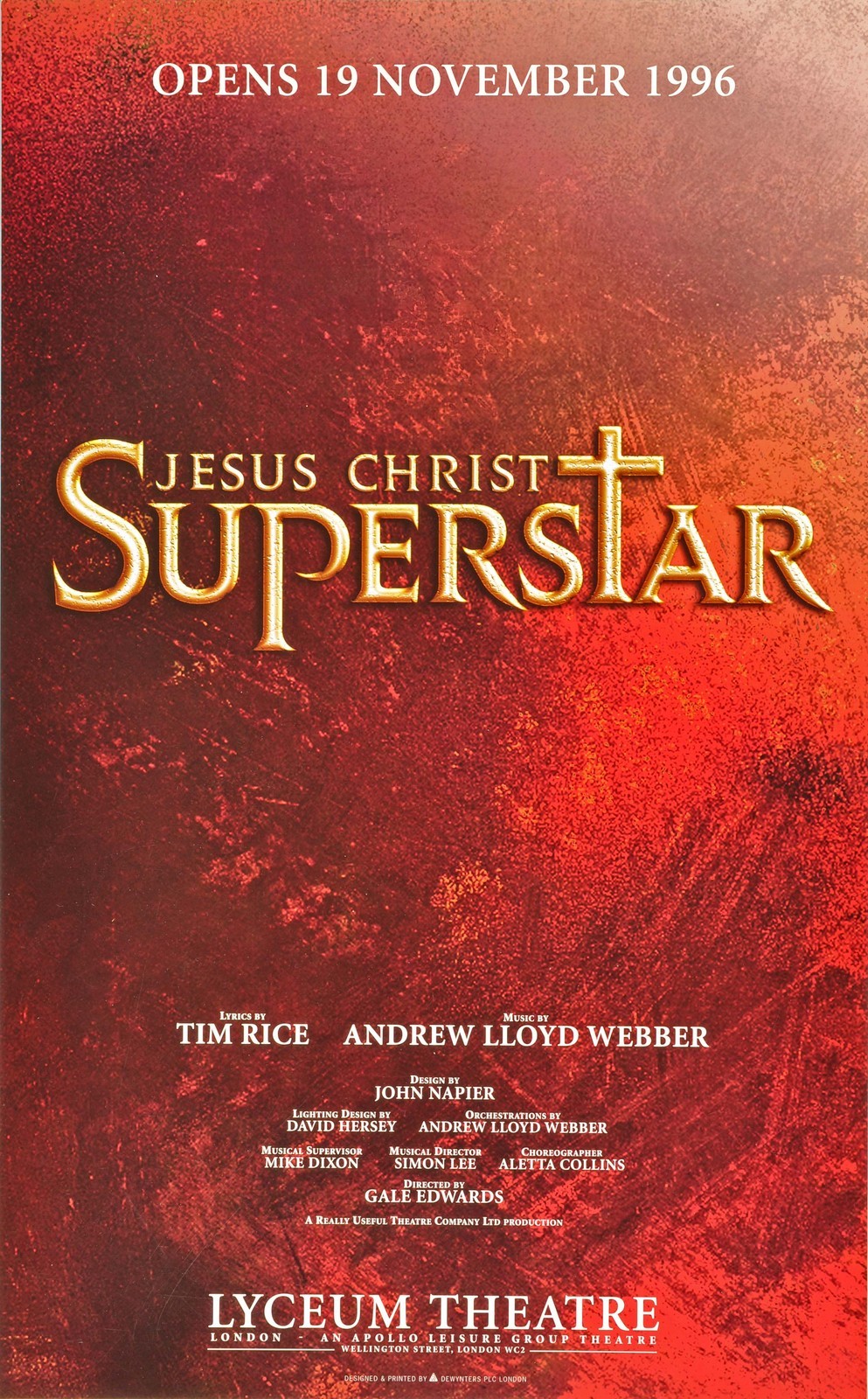

The first production staged here after the reopening was Andrew Lloyd Webber's Jesus Christ Superstar, and since the turn of the century It is Disney Productions' The Lion King that has been filling the house.

1765. Concert and exhibition hall designed by James Paine / 1794. Building converted to theatre use / 1815. Rebuilt by architect Samuel Beazley / 1830. Theatre burnt down; again rebuilt by Beazley. Demolished 1904 / 1904. New theatre designed by Bertie Crewe / 1939. Theatre closed / 1945. Let to Mecca Ltd and opened as a dance hall / 1991-6. Restored by Apollo Leisure Group and reopened as a theatre / Statutorily Listed Historic Building: Grade II*

Infos complémentaires:

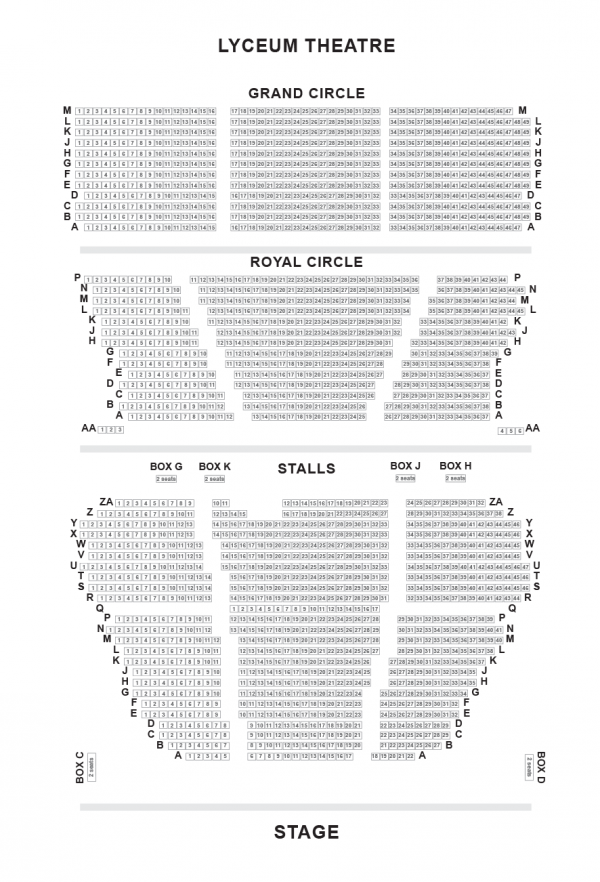

The stalls are divided by two large aisles running the length of the section diagonally through the space. The front half of the stalls is made up of rows A-Q whilst the back half of the section is divided further by two half aisles running horizontally. The Circle overhang does not occur until row Q, meaning the front half is completely unrestricted and not overshadowed. The overhang only begins to affect those seats at the back of the house, which is factored into the pricing structure for the section. Because of the shape of the theatre some seats on the end of rows, particularly those in the first six rows are restricted, something which is again taken into account with their price.

The seats are very gently raked, but enough to allow those at the back a good view of the stage. Due to the interactive nature of The Lion King the stalls are an excellent place to sit with children, especially throughout the stunning opening number. Boxes in the stalls are slightly raised from the level and also provide an interactive experience for the show. Each box has chairs rather than fixed seats which can be moved to allow the best possible view.

The Royal Circle provides excellent views throughout the section, despite being set back towards the back of the auditorium. Leg room on the whole is slightly less than the stalls, so taller audience members may prefer to sit elsewhere for the same price. The overhang begins to affect seats towards the back of the section, and although it does not restrict much of the action it can feel quite far away from the stage. The rake in the Royal Circle can feel severe but this means the safety rail is out of sight for most people, and children are able to see over people’s heads.

Some excellent seats are to be had in the front section of the Royal Circle, towards the centre. Although the section is set quite far back over the stalls, the circle itself feels relatively low meaning a lot of the show happens at just below eye level. With so much action happening all over the stage and even in the auditorium, the Royal Circle is the best place to get an overall panorama of the show.

The Grand or Upper Circle is set high up in the theatre, and with a severe rake can feel unsteady for those who are not good with heights. Although the views are clearest in the front section, Seat Plan advises to sit a couple of rows from the front to avoid the safety bar and have slightly more leg room. The shape of the circle curves more than the lower levels, meaning the ends of each row are identified as restricted view. Handrails on the aisles can affect the view for those sitting towards the middle of each row, although this is mainly a problem in rows A-D.

The section provides excellent views of the stage that are in the main unobstructed. Choose seats towards the centre for a better view, especially those with children who may be easily distracted.

Samuel Beazley’s Greco-Roman portico to Wellington Street / Interior of 1904 by Bertie Crewe

Musical

Original London

1) Lion King (The) (Original London)

Joué durant 20 ans 7 mois 2 semaines actuellement

Première preview: ven. 24 septembre 1999

Première: mar. 19 octobre 1999

Dernière: Open end

Compositeur: Elton John •

Parolier: Tim Rice •

Libettiste: Irene Mecchi • Roger Allers •

Metteur en scène: Julie Taymor •

Chorégraphe: Garth Fagan •

Avec: Josette Bushell-Mingo (Rafifki), Cornell John (Mufasa), Dawn Michael (Sarabi), Daniel Anthony/Ross Coates (Young Simba), Roger Wright (Simba), Rob Edwards (Scar), Simon Gregor (Timon), Martyn Ellis (Pumbaa), Stephanie Charles, Paul J. Medford, Christopher Holt, Paulette Ivory.

Commentaire: Adapted from the Disney film in a brilliant production using masks, puppetry, ballet, music, colour and African rhythms, this musical opened on Broadway in November 1997, and is still running. Having cost some $15 million dollars to stage, the scenery, costumes, puppets, lighting and entire production were hugely praised and it was acclaimed as one of the West End’s greatest ever pieces of theatrical staging. (plus)

Presse: Sarah Hemmings of THE FINANCIAL TIMES says, "As blockbuster musicals go, this is one with beauty and brains."

CHARLES SPENCER of THE DAILY TELEGRAPH" says, "For once a mega musical lives up to the hype. This is a dazzling show with the heart of a lion."

NICHOLAS DE JONGH of THE EVENING STANDARD says, "A beautiful dazzle of invention and imagination."

BENEDICT NIGHTINGALE of THE TIMES says, "Wonder of African jungle is show worth catching."

PETER HEPPLE of THE STAGE says, "This stage version of the Disney animated film is a spectacular delight."

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original

4) Fermeture COVID (Original)

Joué durant 1 an 4 mois

Première preview: 16 March 2020

Première: 16 March 2020

Dernière: 19 July 2021

Compositeur:

Parolier:

Libettiste:

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec:

Commentaire: Tous les théâtres anglais ont dû fermer dès le 16 mars 2020 suite à la pandémide de COVID… (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

3) Oklahoma! (Revival)

Joué durant 5 mois

Nb de représentations: 93 représentations

Première preview: 21 January 1999

Première: 21 January 1999

Dernière: 26 June 1999

Compositeur: Richard Rodgers •

Parolier: Oscar Hammerstein II •

Libettiste: Oscar Hammerstein II •

Metteur en scène: Trevor Nunn •

Chorégraphe: Susan Stroman •

Avec: Maureen Lipman (Aunt Eller), Hugh Jackman (Curly), Josefina Gabrielle (Laurey), Jimmy Johnston (Will Parker), Vicki Simon (Ado Annie), Shuler Hensley (Jud Fry), Peter Polycarpou (AH Hakim), Gavin Lee

Commentaire: With additional funding from Cameron Mackintosh this was a glorious full-scale production, and a sell-out for its National Theatre season, earning the desperately needed money following cuts in the arts grants. Reservations were expressed about whether the subsidised National Theatre should be producing such obviously commercial material, but everyone agreed it was of a standard unlikely to be bettered. Following its sell-out success at the Olivier it was re-staged for a five month run at the Lyceum. (plus)

Presse: MICHAEL COVENEY of THE DAILY MAIL says "A truly great evening."

BENEDICT NIGHTINGALE of THE TIMES says, "Has there ever been a higher standard of dance in any subsidised theatre? No."

CHARLES SPENCER of THE DAILY TELEGRAPH says "The National has a huge hit on its hands."

MICHAEL COVENEY of THE DAILY MAIL says "A truly great evening, easily the equal of Guys and Dolls and Carousel. Enjoy."

NICOLAS DE JONGH of THE EVENING STANDARD was more luke-warm saying " A rich feast of dream-pie, but not my kind of meal".

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Spectacle

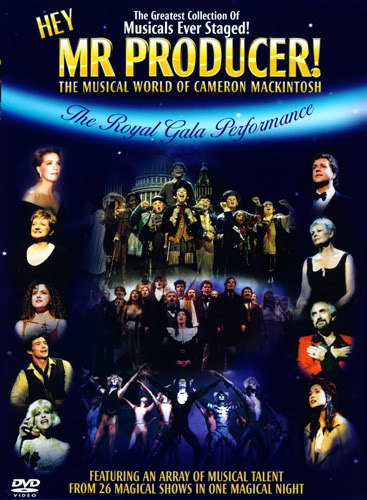

2) Hey Mr Producer ()

Joué durant

Première preview: Inconnu

Première: 07 June 1998

Dernière: 08 June 1998

Compositeur: *** Divers •

Parolier: *** Divers •

Libettiste: *** Divers •

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec:

Commentaire: Tribute to Cameron Mackintosh. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

.png)

.png)