Coliseum Theatre

Londres - Angleterre

Construction: 1904

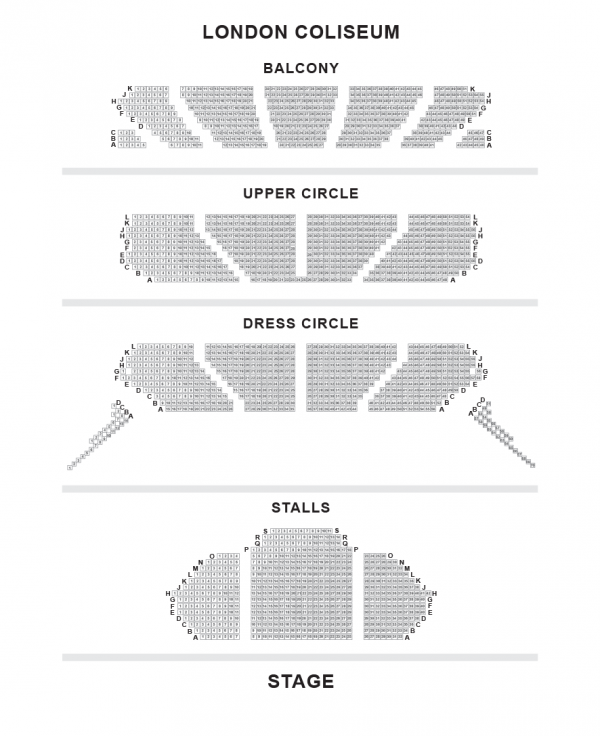

Topologie du théâtre

Nombre de salles actives: 1

Salle 1: (2358) 1904 - Actif

Accès

En métro: Leicester Square

En bus: 3, 6, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 22, 23, 24, 29, 38, 88, 91, 94, 139, 159, 176, 453

Adresse: St. Martin's Lane, London, WC2

Evolution

Bâtiment: The London Coliseum (also known as the Coliseum Theatre) is a theatre on St. Martin's Lane, central London. It is one of London's largest and best-equipped theatres and opened in 1904, designed by theatrical architect Frank Matcham (designer of the London Palladium), for impresario Oswald Stoll. Their ambition was to build the largest and finest music hall, describe as the 'People's palace of entertainment' of its age. It is currently the home of the English National Opera

Nom: London Coliseum

Propriétaire(s)

Remarquable

Matcham’s little-altered masterpiece, a superb variety theatre in the heart of the West End, incorporating every convenience for the comfort of a new breed of theatre-goer.

2358

1904 - Actif

The year was 1902, and the new-found opulence and bravado that came to typify Edwardian London were in full flow. King Edward VII exemplified the art of pleasure-seeking, particularly during the social ‘Season’, lasting from Easter to August, when both English and visiting American society had to be seen ‘in Town’. For lesser mortals the corner pub provided solace among the endless rows of Victorian terraced houses filling out a rapidly expanding suburbia. In both city and suburbs there was ‘new money’ to be found, and elaborate variety theatres were more than ready to charm that money from willing pockets.

This was the background against which a new job came into the Holborn offices of Frank Matcham and Co.: the commission to interpret the ultimate vision of young entrepreneur Oswald (later Sir Oswald) Stoll, who in 1899 had created, with Edward Moss, 15 years his senior, the theatrical operator Moss Empires Ltd. What Stoll wanted was a grand new family-oriented variety theatre, the Theatre de Luxe’ of London, to be built at the foot of St Martin’s Lane, close to Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery. Matcham would certainly have been familiar with the area, having recently added the London Hippodrome (for Moss Empires), nearby in Charing Cross Road, to his tally of over 60 theatres designed and built during the previous 25 years. In the 18th century St Martin's Lane was best known for drinking and fighting, but by 1900 the rather jaded brick-fronted residential buildings on the theatre site, immediately north of the long, narrow Brydges Place (formerly Taylor's Buildings), were free from sin and ripe for redevelopment.

From the site the land falls steadily away to Trafalgar Square with its dominant Nelson’s Column, fountains and pigeons, overlooked by the church of St Martin-in-the-Flelds, James Gibbs's masterpiece of 1722; Matcham would have known that something very special was required of him among such illustrious neighbours. It would be of absolutely no use to create a building that conformed to the rhythm and scale of the existing low-rise architecture; on the other hand, a gargantuan block would be equally inappropriate. Matcham solved the problem brilliantly, dividing the terracotta-faced (now painted) frontage by the deft use of

a triple-arcaded ground storey, restricting its visual height to that of the existing adjacent buildings. His pièce de résistance was the introduction of an exuberant tower above the main entrance, at the southern end of the elevation, topped by a revolving illuminated globe bearing the word ‘coliseum’.

The free baroque asymmetrical façade Is cleverly balanced by a pavilion tower at its northern end, In a relaxed yet controlled design from a man at the peak of his career. The linking body of the theatre Is capped by a continuous balustrade behind which was a refreshment room within a glazed Iron framework, a unique feature In a London theatre; It was removed In 1951. At the end of the 20th century all that remained of this elegant structure were graceful imprints on the tower walls. Entry is via a small, glazed semicircular canopy into an ornate vestibule with banded marble walls under an elaborate Byzantine mosaic dome, signed Diesperser. Oddly, this Byzantine theme Is quickly

abandoned, and the spacious main foyer is comparatively delicate, relying for its welcoming qualities on cream and gold Adamesque ornament. The barrel-vaulted box office was originally a ladies’ powder room.

Stoll's concept at the Coliseum was innovative in every sense, from the lifts provided for the convenience of the audiences to the royal lounge designed to move silently on tracks from the street to the royal box, where it would double as a retiring room. Presumably this did not work well, as it was almost Immediately abandoned in favour of a small retiring room adjacent to the main foyer, redecorated for King George V (from which redecoration an amazing panelled WC and washbasin enclosure survives today), and a second, larger room behind the present royal box. Rising from the main foyer to the simple ‘classical’ dress-circle foyer Is a superb grand staircase of stubby marble balusters and a heavy handrail. Long gone, however, are the, tearooms at all levels, the baronial smoking hall and the state-of-the-art information bureau, a startllngly new Idea in 1902.

The white, cream and gold auditorium, designed to seat over 3,000, is a wonderful three-tier space, richly ornamented in eclectic classical detail. Pairs of bow-fronted boxes under domed canopies adjoin niches originally designed to accommodate an auditorium choir, but now converted to boxes. Over the whole stretches a fine domed celling. Matcham was no stranger to modern engineering practices, and the cantilevered balconies make use of the finest early 20th-century technology.

Behind the proscenium arch, the Coliseum is quite massive in scale. It was originally fitted out with a triple revolve incorporating an outer table 75 feet in diameter, all of which was removed in 1977. Seventy- one counterweight sets were provided, along with 10 sets of two-ton counterweights intended to raise heavy props. In the 1970s a cyclorama track was in situ on the rear wall, but this was seen In pieces, lying on the stage of the disused Alexandra Palace Theatre in north London - where it was almost certainly removed In a compromise effort to preserve it, there being In the late 1990s a sadly unfulfilled move to create a Museum of Theatre Technology.

Ellen Terry, Sarah Bernhardt and Dlaghilev all appeared at the Coliseum in its early 20th-century glory days. Later, for seven years from 1961, it was used as a cinema before becoming home to the Sadler's Wells Opera Company, now the English National Opera. Long may It continue to be so.

Lack of finance over decades saw the theatre in what seemed to be an unstoppable decline. But with a life-saving Heritage Lottery Fund contribution, and the artistry of Nick Thompson of RHWL Architects, the beauty of Matcham’s glorious design was again revealed, both internally and externally, on 21 February 2004, to open with The Rhinegold.

The London Coliseum (also known as the Coliseum Theatre) is a theatre on St. Martin's Lane, central London. It is one of London's largest and best-equipped theatres and opened in 1904, designed by theatrical architect Frank Matcham (designer of the London Palladium), for impresario Oswald Stoll. Their ambition was to build the largest and finest music hall, describe as the 'People's palace of entertainment' of its age. It is currently the home of the English National Opera

London Coliseum

Matcham’s little-altered masterpiece, a superb variety theatre in the heart of the West End, incorporating every convenience for the comfort of a new breed of theatre-goer.

Musical

Revival

34) Hairspray (Revival)

Joué durant 4 mois 1 semaine

Première preview: 23 April 2020

Première: 23 April 2020

Dernière: 29 August 2020

Compositeur: Marc Shaiman •

Parolier: Marc Shaiman • Scott Wittman •

Libettiste: Mark O'Donnell • Thomas Meehan •

Metteur en scène: Jack O'Brien •

Chorégraphe: Jerry Mitchell •

Avec: Michael Ball, Marisha Wallace, Lizzie Bea

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original

33) Fermeture COVID (Original)

Joué durant 1 an 4 mois

Première preview: 16 March 2020

Première: 16 March 2020

Dernière: 19 July 2021

Compositeur:

Parolier:

Libettiste:

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec:

Commentaire: Tous les théâtres anglais ont dû fermer dès le 16 mars 2020 suite à la pandémide de COVID… (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Concert

32) Pirate Queen (The) (Concert)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 1 représentations

Première preview: 23 February 2020

Première: 23 February 2020

Dernière: 23 February 2020

Compositeur: Claude-Michel Schonberg •

Parolier: Alain Boublil • Claude-Michel Schonberg •

Libettiste: Alain Boublil • Claude-Michel Schonberg •

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Rachel Tucker (Grace O'Malley), Jai McDowall (Tiernan), Matt Pagan (Donal)

Commentaire: A charity concert production with proceeds to Leukaemia UK. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

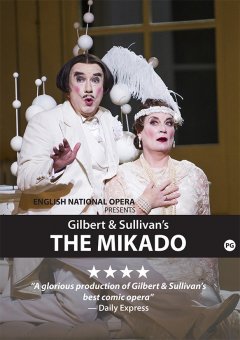

31) Mikado (The) (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Nb de représentations: 9 représentations

Première preview: 28 October 2019

Première: 28 October 2019

Dernière: 30 November 2019

Compositeur: Arthur Sullivan •

Parolier: W.S. Gilbert •

Libettiste: W.S. Gilbert •

Metteur en scène: Jonathan Miller •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: John Tomlinson, Elgan Llŷr Thomas, Richard Suart, Andrew Shore, Ben McAteer, Soraya Mafi, Sioned Gwen Davies and Yvonne Howard.

Commentaire: Une production de l'ENO (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

30) On Your Feet! (Revival)

Joué durant 2 mois 2 semaines

Première preview: 14 June 2019

Première: 14 June 2019

Dernière: 31 August 2019

Compositeur: Emilio Estefan • Gloria Estefan •

Parolier: Emilio Estefan • Gloria Estefan •

Libettiste: Alexander Dinelaris •

Metteur en scène: Jerry Mitchell •

Chorégraphe: Sergio Trujillo •

Avec:

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

29) Notre-Dame de Paris (Revival)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 7 représentations

Première preview: 23 January 2019

Première: 23 January 2019

Dernière: 27 January 2019

Compositeur: Richard Cocciante •

Parolier: Luc Plamondon •

Libettiste: Victor Hugo •

Metteur en scène: Gilles Maheu •

Chorégraphe: Martino Muller •

Avec: Angelo Del Vecchio (Quasimodo), Hiba Tawaji (Esmeralda), Daniel Lavoie (Frollo), Richard Charest (Gringoire), Alyzee Lalande, Idesse (both Fleur-de-Lys), Martin Giroux (Phoebus), Jay (Clopin).

Commentaire: The original French production will be performed in London with English surtitles (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

28) Porgy and Bess (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois 1 semaine

Première preview: 11 October 2018

Première: 11 October 2018

Dernière: 17 November 2018

Compositeur: George Gershwin •

Parolier: DuBose Heyward • Ira Gershwin •

Libettiste: DuBose Heyward •

Metteur en scène: James Robinson •

Chorégraphe: Dianne McIntyre •

Avec: Eric Greene (Porgy), Nicole Cabell (Bess), Nmon Ford (Crown), Latonia Moore (Serena), Gweneth-Ann Rand (Serena) - Oct 27/31/Nov 10), Nadine Benjamin (Clara), Tichina Vaughn (Maria), Donovan Singletary (Jake), Frederick Ballentine (Sporting Life), Rheinaldt Tshepo Moagi (Mingo), Chaz'men Williams-Ali (Robbins/Crab Man), Byron Jackson (Frazier), Sarah-Jane Lewis (Annie), Nozuko Teto (Strawberry Woman), Njabulo Madlala (Jim), Whitaker Mills (Undertaker), Thando Mjandana (Nelson).

Commentaire: More than 80 years after its premiere, Porgy and Bess receives its first ENO staging. Written for a large cast, with a 40-voice chorus specially formed for this production, and full orchestra, Porgy and Bess is infused with unforgettable melodies, including the much-loved ‘Summertime’. This is a stage work that is emotionally charged, powerful and moving, delivered through jazz, ragtime, blues and spirituals. (plus)

Presse: “Thrilling... spine-tingling” The Times

“Electrifying... does Gershwin proud" The Independent

"This is how to do it" The Guardian

“Should not be missed” The Arts Desk

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

27) Chess (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Première preview: 26 April 2018

Première: 01 May 2018

Dernière: 02 June 2018

Compositeur: Benny Andersson • Björn Ulvaeus •

Parolier: Tim Rice •

Libettiste: Richard Nelson •

Metteur en scène: Laurence Connor •

Chorégraphe: Stephen Mear •

Avec:

Commentaire: Landmark musical in first major West End revival in over 30 years. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

26) Iolanthe (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois 3 semaines

Première preview: 13 February 2018

Première: 13 February 2018

Dernière: 07 April 2018

Compositeur: Arthur Sullivan •

Parolier: W.S. Gilbert •

Libettiste: W.S. Gilbert •

Metteur en scène: Cal McCrystal •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Samantha Price, Ellie Laugharne, Yvonne Howard, Marcus Farnsworth

Commentaire: Cal McCrystal (One Man, Two Guvnors) directs a production that embraces the chaotic physical comedy and irreverence that are his hallmarks. Outstanding young mezzo-soprano and ENO Harewood Artist Samantha Price leads a cast of ENO favourites, including Andrew Shore as the Lord Chancellor. (plus)

Presse: ‘If you're not crying with laughter, visit your GP’ The Arts Desk

‘A grand and gorgeous extravaganza’ The Telegraph

‘An all-round, knockout success’ Financial Times

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

25) Kiss me Kate (Revival)

Joué durant 1 an 1 semaine

Première preview: 20 June 2018

Première: 20 June 2017

Dernière: 30 June 2018

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: Bella Spewack • Samuel Spewack •

Metteur en scène: Jo Davies •

Chorégraphe: Will Tuckett •

Avec: Quirijn de Lang (Fred Graham/Petruchio), Stephanie Corley (Lilli Vanessi/Katharine), Zoe Rainey (Lois Lane/Bianca), Alan Burkitt (Bill Calhoun/Lucentio), Jack Wilcox (Hortensio), Aiesha Pease (Hattie), Stephane Anelli (Paul), Joseph Shovelton (Gunman), John Savournin (Gunman), James Hayes (Harry Trevor/Baptista), Malcolm Ridley (Harrison Howell), Claire Pascoe (Ralph - Stage Manager), Michelle Andrews (dancer), Rachael Crocker (dancer), Freya Field (dancer), Kate Ivory Jordan (dancer), Harrison Clark (dancer), Jordan Livesey (dancer), Ben Oliver (dancer), Ross Russell (dancer).

Commentaire: Opera North most recently revived Kiss Me Kate in a new production directed by Jo Davies and choreographed by Will Tuckett. Co-produced with the Welsh National Opera, it played as part of the the celebrations of Shakespeare 400 and opened at the Leeds Grand Theatre in September 2015 before touring to Theatre Royal Newcastle, The Lowry Salford, and Theatre Royal Nottingham. The production returns to the Leeds Grand Theatre in May 2018. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original

24) Bat Out of Hell (Original)

Joué durant 2 mois

Première preview: 05 June 2017

Première: 20 June 2017

Dernière: 22 August 2017

Compositeur: Jim Steinman •

Parolier: Jim Steinman •

Libettiste: Jim Steinman •

Metteur en scène: Jay Scheib •

Chorégraphe: Emma Portner •

Avec:

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

23) Sunset Boulevard (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Première preview: 01 April 2016

Première: 04 April 2016

Dernière: 07 May 2016

Compositeur: Andrew Lloyd Webber •

Parolier: Christopher Hampton • Don Black •

Libettiste: Christopher Hampton • Don Black •

Metteur en scène: Lonny Price •

Chorégraphe: Stephen Mear •

Avec: Glenn Close (Norma Desmond), Michael Xavier (Joe Gillis), Siobhan Dillon (Betty Shaefer), Fred Johanson (Max), Julian Forsyth (Cecil B DeMille), Mark Goldthorp (Sheldrake), Fenton Gray (Manfred), Haydn Oakley (Artie Green), James Paterson (Jonesy), Carly Anderson, Michelle Bishop, Jacob Chapman, Nadeem Crowe, Cornelia Farnsworth, Ria Jones, Katie Kerr, Aaron Lee Lambert, Matthew McKenna, Jo Morris, Tanya Robb, Ashley Robinson, Vicki Lee Taylor, Gary Tushaw, Adam Vaughan and Stuart Winter.

Commentaire:

Presse: "Thrill a minute... Triumphant" - Daily Telegraph

"The most sumptuous sound I've heard in a musical" The Guardian

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

22) Mikado (The) (Revival)

Joué durant 2 mois 2 semaines

Première preview: 21 November 2015

Première: 21 November 2015

Dernière: 06 February 2016

Compositeur: Arthur Sullivan •

Parolier: W.S. Gilbert •

Libettiste: W.S. Gilbert •

Metteur en scène: Jonathan Miller • Elaine Tyler-Hall •

Chorégraphe: Anthony Van Laast •

Avec: Richard Suart (Ko-Ko), Anthony Gregory (Nanki-Poo), Mary Bevan (Yum-Yum), Graeme Danby (Pooh-Bah), Yvonne Howard (Katisha), Robert Lloyd (The Mikado of Japan), George Humphreys (Pish-Tush), Rachael Lloyd (Pitti-Sing)

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Opéra

Revival

21) Traviata (La) (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Première preview: 09 February 2015

Première: 09 February 2015

Dernière: 13 March 2015

Compositeur: *** Divers •

Parolier: *** Divers •

Libettiste: *** Divers •

Metteur en scène: Peter Konwitschny •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Elizabeth Zharoff (Violetta), Ben Johson (Alfredo), Anthony Michaels-Moore, Clare Presland (Flora), Paul Hopwood (Gaston), Matthew Hargreaves (Baron Douphol), Charles Johnston (Marquis d'Obigny), Martin Lamb (Dr Grenvil), Valerie Reid (Annina)

Commentaire: Amongst the most popular of Verdi's operas, La traviata is the work of a master of the musical drama. Its perfumed arias and soaring choruses vividly depict the ravishingly decadent but glamorous world of Parisian high society as the background to a heart rending story of romantic happiness destroyed. Original book called La Dame aux Camelias. Sung in English with English surtitles.

Une production de l'ENO (English National Opera) (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Musical

Revival

20) Kismet (Revival)

Joué durant 2 semaines

Nb de représentations: 19 représentations

Première preview: 26 June 2007

Première: 27 June 2007

Dernière: 14 July 2007

Compositeur: George Forrest • Robert Wright •

Parolier: George Forrest • Robert Wright •

Libettiste: Charles Lederer • Luther Davis •

Metteur en scène: Gary Griffin •

Chorégraphe: Nikki Woollaston •

Avec: Hajj/Poet ... Michael Ball / Lalume ... Faith Prince / Marsinah ... Sarah Tynan / Imam ... Donald Maxwell / Wazir ... Graeme Danby / Caliph ... Alfie Boe / Chief Policeman ... Rodney Clarke

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

19) On the Town (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Première preview: 20 April 2007

Première: 20 April 2007

Dernière: 25 May 2007

Compositeur: Leonard Bernstein •

Parolier: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Libettiste: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Metteur en scène: Jude Kelly •

Chorégraphe: Stephen Mear •

Avec: Helen Anker (Ivy Smith), Caroline O’Connor (Hildegarde Esterhazy), Lucy Schauffer (Clair DeLoon), Ryan Molloy (Ozzie), Joshua Dallas (Gabey), Sean Palmer ( Chip Offenbloch), Andrew Shore/Graeme Danby (Judge), Janine Duvitski (Lucy), June Whitfield (Madame Dilly), Rodney Clarke (Master of Ceremonies), Alison Jiear, Julia Hinchcliffe

Commentaire: In 2005 when this revival was first staged, there was some fuss about whether the country’s National “opera” should be presenting a Broadway “musical”. Any doubts were answered by sell-out shows and the ENO having to stage extra performances to meet the demand for tickets. This was a straight-forward revival of that earlier success, with some cast changes – especially the three principal sailors, and the introduction of June Whitefield into the small but telling role as the deliciously tipsy Madame Dilly. One or two critics continued to moan about the suitability of this show at an “opera house”, but overall it was highly praised and once more a total sell-out. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

18) On the Town (Revival)

Joué durant 2 mois 2 semaines

Nb de représentations: 17 représentations

Première preview: 05 March 2005

Première: 10 March 2005

Dernière: 28 May 2005

Compositeur: Leonard Bernstein •

Parolier: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Libettiste: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Metteur en scène: Jude Kelly •

Chorégraphe: Stephen Mear •

Avec: Willard W. White (Workman), Helen Anker (Ivy Smith), Caroline O’Connor (Hildegarde Esterhazy), Lucy Schauffer (Clair DeLoon), Timothy Howar (Ozzie), Aaron Lazar (Gabey), Adam Garcia (Chip Offenbloch), Andrew Shore (Judge), Janine Duvitski (Lucy), Sylvia Syms, Alison Jiear, Rodney Clarke, Greg Winter, Tom Dwyer

Commentaire: With the exception of the veteran Willard W. White in a very small role, the cast for this show did not contain any of the ENO’s regular company, and, primarily, was a dance show rather than a singing show. This raised a lot of questions as to why the country’s National “opera” should be presenting a show performed by imported West End singers and dancers, and should have installed a £100,000 sound system for just 17 performances. However, everyone agreed it was a worthwhile revival after more than 40 years, and it proved highly popular, selling out the enormous Coliseum with no difficulty. (plus)

Presse: Independent: "On the Town is bang on the money"

Music & Vision: "Sex and art"

ConcertoNet (English): "The young things could all have learnt a trick or two from the old hands"

Financial Times: "It is about time ENO started to cash in on the market for musicals"

The Observer: "Bernstein's On the Town hasn't been staged for years for good reason"

Musical Pointers: "A curious choice for an important ENO production"

The Times: "Dramatic clichés don’t make a show"

Guardian Unlimited: "An evening uneven in tone and inspiration"

Music OMH: "The result is electric"

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

17) Street Scene (Original London)

Joué durant

Première preview: 12 October 1989

Première: 12 October 1989

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Kurt Weill •

Parolier: Langston Hughes •

Libettiste: Elmer Rice •

Metteur en scène: David Pountney •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Abraham Kaplan ... Terry Jenkins / Greta Fiorentino ... Susan Bullock / Salvation Army Girl ... Marian Martin / ... Melodie Waddingham / Carl Olsen ... Arwel Huw Morgan / Emma Jones ... Meriel Dickinson / Olga Olsen ... Angela Hickey / Shirley Kaplan ... Blythe Duff / Henry Davis ... Neil Patterson / Willie Maurrant ... Daniel Ison

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

16) Pacific Overtures (Original London)

Joué durant 2 mois 2 semaines

Nb de représentations: 27 représentations

Première preview: 10 September 1987

Première: 10 September 1987

Dernière: 26 November 1987

Compositeur: Stephen Sondheim •

Parolier: Stephen Sondheim •

Libettiste: John Weidman •

Metteur en scène: Keith Warner •

Chorégraphe: David Toguri •

Avec: Richard Angas (Reciter), Malcolm Rivers (Kayama), Christopher Booth-Jones (Manjiro), John Kitchiner (Lord Abe), Graham Fletcher (Commodore Perry), Michael Sadler (Tamate), Simon Masterton-Smith (The Shogun’s Mother), Terry Jenkins (Madam)

Commentaire: This revolutionary work had a musical score which started with the haunting and mournful sounds of shamisen, shakuhachi and Japanese tonal ranges and gradually, as the country became more Westernised, so did the music - until the final scene is one of frantic heavy rock. It was a history of Japan written from the viewpoint of the Japanese and performed in the style of Kabuki Theatre, with “invisible” stage hands, all the women’s roles played by men, and a “reciter” who comments on the action, reciting the occasional haiku. The critics split exactly in half: it was the most astonishing, original, exciting, profound and brilliant musical; it was a pretty but incomprehensible bore. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

15) Kiss me Kate (Revival)

Joué durant 1 mois

Nb de preview: 1 previews

Première preview: 23 December 1970

Première: 24 December 1970

Dernière: 23 January 1971

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: Bella Spewack • Samuel Spewack •

Metteur en scène: Peter Coe •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Emile Belcourt (Fred Graham), Ann Howard (Lili), Eric Shilling (Harry), Francis Egerton & John Bluthall (Gangsters)

Commentaire: Ce premier revival a été une présentation du Sadler’s Wells Opera avec le dialogue «anglicisé» pour le rendre plus acceptable pour le public anglais! Il a eu un très court passage à travers la saison de Noël. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

14) Aladdin (Porter) (Revival)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 145 représentations

Première preview: 17 December 1959

Première: 17 December 1959

Dernière: 1960

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: S.J. Perelman •

Metteur en scène: Robert Helpmann •

Chorégraphe: Robert Helpmann •

Avec: Bob Monkhouse (Aladdin), Doretta Morrow (The Princess), Ronald Shiner (Widow Twankey), Ian Wallace (The Emperor), Alan Wheatley (Abanazar), Anne Heaton (The Diamond Fairy), David Fallon (Grand Vizier), Philip Hogan (Wishee), Eddie Sargent (Washee), Jacqueline Marygold, Golda Casimir, Jessie Carron, Milton Reid, Kerry Jordan, Reginald Barratt, Mollie Hare and Geoffrey Webb

Commentaire: Adaptation à la scène de la création américaine à la TV en 1958 (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

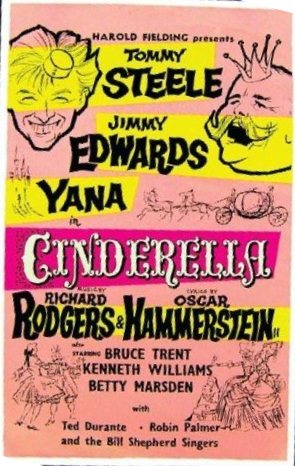

13) Cinderella (Revival)

Joué durant

Première preview: 18 December 1958

Première: 18 December 1958

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Richard Rodgers •

Parolier: Oscar Hammerstein II •

Libettiste: Oscar Hammerstein II •

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Avec: Ted Durante, Jimmy Edwards, Enid Lowe, Betty Marsden, Robin Palmer, Tommy Steele, Bruce Trent, Kenneth Williams, Yana

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

12) Bells are ringing (Original London)

Joué durant 8 mois 2 semaines

Nb de représentations: 292 représentations

Première preview: 14 November 1957

Première: 14 November 1957

Dernière: 28 July 1958

Compositeur: Jule Styne •

Parolier: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Libettiste: Adolph Green • Betty Comden •

Metteur en scène: Jerome Robbins • Bob Fosse •

Chorégraphe: Jerome Robbins • Bob Fosse •

Avec: Sue Summers ... Jean St. Clair / Gwynne ... Allyn McLerie / Ella Peterson ... Janet Blair / Carl ... Harry Naughton / Inspector Barnes ... Donald Stewart / Francis ... C. Denier Warren / Sandor ... Eddie Molloy / Jeff Moss ... George Gaynes / Larry Hastings ... Robert Henderson / Telephone Man ... Keith Galloway

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

11) Damn Yankees (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 258 représentations

Première preview: 28 March 1957

Première: 28 March 1957

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Richard Adler •

Parolier: Jerry Ross •

Libettiste: Douglas Wallop • George Abott •

Metteur en scène: George Abbott •

Chorégraphe: Bob Fosse •

Avec: Lola … Belita

Applegate … Bill Kerr

Joe Hardy … Ivor Emmanuel

Meg … Betty Paul

Ensemble … Donald Stewart, Robin Hunter

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

10) Pajama Game (The) (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 588 représentations

Première preview: 13 October 1955

Première: 13 October 1955

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Jerry Ross • Richard Adler •

Parolier: Jerry Ross • Richard Adler •

Libettiste: George Abott • Richard Bissell •

Metteur en scène: George Abbott • Jerome Robbins •

Chorégraphe: Bob Fosse •

Avec: Max Wall (Hines), Frank Lawless (Prez), Felix Felton (Hasler), Edmund Hockridge (Sid Sorokin), Elizabeth Seal (Gladys), Joan Emney (Mabel), Joy Nichols (Babe Williams), Jessie Robins (Mae), Olga Lowe (Brenda), Arthur Lowe (Salesman)

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

9) Can-Can (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 394 représentations

Première preview: Inconnu

Première: 14 October 1954

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: Abe Burrows •

Metteur en scène: Abe Burrows •

Chorégraphe: Michael Kidd •

Avec: Bailiff ... Bernard Quinn

Registrar ... Richard Lawrence

Policemen ... George Pastell

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

8) Guys and Dolls (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 555 représentations

Première preview: 28 May 1953

Première: 28 May 1953

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Frank Loesser •

Parolier: Frank Loesser •

Libettiste: Abe Burrows • Jo Swerling •

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec:

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

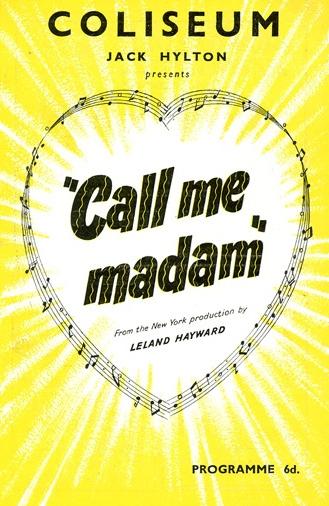

7) Call Me Madam (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 486 représentations

Première preview: Inconnu

Première: 15 March 1952

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Irving Berlin •

Parolier: Irving Berlin •

Libettiste: Howard Lindsay • Russel Crouse •

Metteur en scène: Richard Bird •

Chorégraphe: George Carden •

Avec: Mrs. Sally Adams ... Billie Worth

The Secretary of State ... Robert Henderson

Supreme Court Justice ... Mayne Lynton

Congressman Wilkins ... Sidney Keith

Henry Gibson ... David Storm

Kenneth Gibson ... Jeff Warren

Senator Gallagher ... Launce Maraschel

Secretary To Mrs. Adams ... Mary Dean

Butler ... Richard Courtney

Senator Brockbank ... Arthur Lowe

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

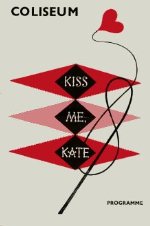

6) Kiss me Kate (Original London)

Joué durant 11 mois 3 semaines

Nb de représentations: 400 représentations

Première preview: 08 March 1951

Première: 08 March 1951

Dernière: 23 February 1952

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: Bella Spewack • Samuel Spewack •

Metteur en scène: John C. Wilson •

Chorégraphe: Hanya Holm •

Avec:

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

5) Annie get your gun (Original London)

Joué durant

Nb de représentations: 1304 représentations

Première preview: Inconnu

Première: 07 June 1947

Dernière: Inconnu

Compositeur: Irving Berlin •

Parolier: Irving Berlin •

Libettiste: Dorothy Fields • Herbert Fields •

Metteur en scène: Joshua Logan •

Chorégraphe: Helen Tamiris •

Avec:

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Original London

4) Something for the Boys (Original London)

Joué durant 1 mois 2 semaines

Première preview: 30 March 1944

Première: 30 March 1944

Dernière: 20 May 1944

Compositeur: Cole Porter •

Parolier: Cole Porter •

Libettiste: Dorothy Fields • Herbert Fields •

Metteur en scène: Frank P. Adey •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Evelyn Dall (Blossom), Daphne Barker (Chiquita), Bobby Wright (Harry), Harry Moreny (Colonel Grubbs), Leigh Stafford (Rocky Fulton), Marianne Davis (Melanie)

Commentaire: La production britannique a commencé une tournée Try-Out avant Londres

à Glasgow. Mais son arrivée à Londres fin mars n'a pas été couronnée de succès et la spectacle s'est arrêté très rapidement, après sept semaines et quelques jours seulement, le 20 mai 1944. (plus)

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Musical

Revival

3) Maid of the Mountains (The) (Revival)

Joué durant 5 mois 2 semaines

Nb de représentations: 224 représentations

Première preview: 01 April 1942

Première: 01 April 1942

Dernière: 12 September 1942

Compositeur: Harold Fraser-Simon •

Parolier: Harry Graham •

Libettiste: Frédéric Lonsdale •

Metteur en scène: Emilie Littler •

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Sylvia Cecil (Teresa), Malcolm Keen (Baldasarre), Dan Noble (Beppo), Sonnie Hale (Antonio), Elsie Randolph (Vittoria), Davy Burnaby (General Malona)

Commentaire:

Presse: "Without José Collins, star of the 1917 production, there is no pretending that the entertainment is the same thing” (Times).

Stage said that the piece had been “slightly modernized by the introduction of a few topical touches.”

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

Revue

Original

2) Blackbirds of 1935 (Original)

Joué durant 2 mois 1 semaine

Nb de représentations: 123 représentations

Première preview: 20 December 1934

Première: 20 December 1934

Dernière: 02 March 1935

Compositeur:

Parolier:

Libettiste:

Metteur en scène:

Chorégraphe:

Avec: Tim Moore, Nyas Berry, Peg Leg Bates, Four Cobs, Blackbird Choir, Pike Davis and his Continental Orchestra, Walter Batie, Blue McAllister, George Williams, Toney Ellis, Louis Sharp, De Lloyd Mckaye, Jack Hilliard, Willie Jones, William Allen, Eddie Johnson, Sunny Austin, Eddie Dent. Valaida, Edith Wilson, Kahloah.

Commentaire:

Presse:

Plus d'infos sur cette production:

Plus d'infos sur ce musical

.png)

.png)