Allegro

Musical (1947)

Allegro est un musical de Richard Rodgers (musique) et Oscar Hammerstein II (livret et paroles), leur troisième collaboration pour la scène. Présenté à Broadway le 10 octobre 1947, la musical est centré sur la vie de Joseph Taylor, Jr. – Joe suit les traces de son père en tant que médecin, mais est tenté par la fortune et la célébrité dans un hôpital d’une grande ville.

Après les immenses succès des deux premiers musicale de Rodgers et Hammerstein, Oklahoma! et Carousel, le duo a cherché un sujet pour leur prochaine pièce. Hammerstein avait longtemps envisagé un travail sérieux qui traiterait des problèmes de l’homme ordinaire dans le monde moderne en évolution rapide. Lui et Rodgers ont cherché à créer une œuvre qui serait aussi innovante que leurs deux premiers musicals. À cette fin, ils ont créé une pièce avec une grande distribution, y compris un chœur grec. La production n’aurait pas de décors. Des accessoires et des projections servaient à suggérer des emplacements.

Après un Try-Out désastreux à New Haven, dans le Connecticut, le musical a ouvert ses portes à Broadway avec une grande prévente de billets et des critiques très mitigées. Agnes de Mille, la chorégraphe des précédentes productions de Rodgers et Hammerstein à Broadway, a à la fois mis en scène et chorégraphié l’œuvre. Le spectacle a été considéré comme trop moralisateur, et la représentation à Broadway s’est terminée après neuf mois. Il a été suivi d’une courte tournée nationale. Il n’a pas eu de production dans le West End et a rarement été relancé. Allegro a été enregistré deux fois, l’album original de la distribution et un enregistrement studio sorti en 2009.

Voir liens dossier ci-dessous…

Allegro raconte la vie d’un homme ordinaire – Joseph Taylor, Jr. – depuis sa naissance, en passant per son enfance, ses années d’université, son mariage, sa carrière médicale et son déménagement dans la «grande ville». À l’âge mûr, Joe est soudainement confronté à un moment de crise. Il remet en question ses décisions de vie et décide de retourner sur son lieu de naissance. Tout au long du voyage, les relations de Joe avec sa famille, ses amis et ses collègues éclairent les thèmes de l’ambition, de la compétition et de l’humanité de la série.

Afficher le synopsis détaillé

A.1) Acte I

En 1905, le médecin d'une petite ville Joseph Taylor et son épouse Marjorie célèbrent la naissance de leur fils (Joseph Taylor, Jr.). Les habitants de la ville prédisent de grandes choses pour Joseph Taylor Jr., ou Joe comme on l'appellera. Alors que le Dr Taylor retourne au travail, il imagine son fils Joe grandir pour devenir médecin comme lui. Grand-mère, assise avec bébé Joe, anticipe la joie de voir un autre petit garçon devenir un homme (I Know It Can Happen Again).

Baby Joe vit toutes ses premières expériences sensorielles: manger, jouer avec un hochet, créer une distinction entre sa mère et son père, voir son père partir avec son sac tous les jours tandis que sa mère l'embrasse pour lui dire au revoir, et la présence d'une autre silhouette qui ne sent pas aussi bon et qui s'en va toujours dès qu'il récupère son sac noir. Grand-mère remarque Joe debout seul pour la première fois et appelle Marjorie avec enthousiasme pour être témoin de la nouvelle conquête du garçon. Ensemble, ils regardent Joe faire ses premiers pas et célèbrent son accomplissement capital (One Foot, Other Foot).

Une séquence de danse emmène Joe Jr. à travers son enfance, y compris la rencontre de Jennie Brinker, fille d'un homme d'affaires et amie des Taylor. A la fin de la danse, les enfants se disent bonsoir. Lorsque la grand-mère de Joe meurt, Jennie tient compagnie à Joe à la maison au lieu d'aller jouer dehors.

Les années passent (Winters Go By) et Joe est maintenant au lycée et sort avec Jennie. Déconcerté et nerveux à l’idée d’interagir avec le sexe opposé, Joe ne trouve pas la confiance nécessaire pour l’embrasser (Poor Joe). Aujourd'hui âgé de 17 ans, Joe est à l'université et espère devenir médecin comme son père. Juste avant de partir, il écoute ses parents depuis sa chambre rêver de ce qu'il deviendra et de la fille qu'il épousera (A Fellow Needs A Girl).

À l'université, Joe assiste à la danse Freshman Get Together dans le gymnase (Freshman Dance). C’est la première fois où l’on voit Joe en scène, jusqu’alors il n’a été qu’évoqué! Alors que d’autres autour de lui semblent s’épanouir, Joe, impressionné par la vie universitaire sur le campus, reste un peu solitaire (Darn Nice Campus). Lors d’un rassemblement d’encouragement, les étudiants chantent The Football Song. Joe est embarrassé lorsqu’il chante une chanson dialoguée et se trompe à plusieurs reprises (Wildcats) et s’en va démoralisé. Plus tard, Charlie Townsend, la star de première année de l'équipe de football universitaire, s'approche de Joe, remarquant qu'ils partagent en grande partie les mêmes cours et qu'ils sont tous deux sur la voie pré-médicale. Charlie demande s'il peut emprunter les notes de Joe et l'invite dans sa maison de fraternité, laissant Joe ravi.

Pendant que Joe est à l'université, Jennie reste à la maison et son riche père, Ned Brinker, qui désapprouve Joe pour avoir passé tant d'années à l'école avant de gagner sa vie, l'encourage à trouver d'autres petits amis. Jennie lit une lettre de Joe à son ami Hazel (A Darn Nice Campus - Reprise). Hazel plaint Jennie d'avoir courtisé un garçon dont la mère a une telle influence sur lui.

Alors que Charlie Townsend, maintenant le colocataire de Joe, sort pour un rendez-vous, Joe refuse de le rejoindre afin de pouvoir se concentrer sur ses devoirs. Il ne pense qu'à Jennie chez lui, la seule fille avec qui il soit sorti. Charlie Townsend part après avoir dit à Joe de laisser les devoirs pour qu'il les copie.

Au fil du temps, Joe se concentre sur la chimie, l'anglais, la biologie, la philosophie et le grec, tout en conservant les lettres de Jennie, qui continue de le tenir au courant des autres couples de son âge déjà mariés et ayant des enfants dans leur nouvelle maison. Elle part en Europe avec son père et rencontre un nouvel homme nommé Bertram. Au fur et à mesure que leur relation progresse, Joe décide qu'il est temps de «se détacher» de Jennie et demande à Charlie Townsend de le mettre en relation avec la sœur de sa petite amie, Beulah.

Après un rendez-vous à quatre avec Charlie Townsend et sa petite amie Molly, Joe et Beulah se retrouvent seuls ensemble. Beulah est charmée par les qualités douces et romantiques de Joe, et les deux apprennent à se connaître (So Far). Quand ils commencent à s'embrasser, Joe ne peut s'empêcher de penser à Jennie. Il finit par s'endormir au milieu de leur rendez-vous, offensant Beulah. Elle s'éloigne avec dégoût…

Le lendemain, Joe reçoit une lettre de Jennie expliquant qu'elle en a fini avec Bertram et qu'elle rentrera à la maison en juillet en attendant le retour de Joe. Impatient de passer les mois de mai et juin, Joe est déterminé à se concentrer à nouveau sur son mariage avec Jennie. Lorsqu'ils se retrouvent, Joe avoue qu'il n'a jamais cessé de penser à elle (You Are Never Away). Mais lorsque Joe commence à parler de son rêve d’aider les patients à guérir, Jennie semble déçue par la perspective de devoir d'attendre que Joe devienne médecin pour pouvoir l’épouser. Joe dit qu'ils pourraient se marier avant cette date. Mais Jennie mentionne un emploi bien rémunéré que son père a dans son entreprise en pleine croissance de charbon et de bois. Joe doit se décider (Pauvre Joe - Reprise).

Autour de limonades, M. Brinker laisse entendre que Joe pourrait avoir de plus grandes ambitions que de soutenir le rêve de son père de diriger un petit hôpital. De son côté, Marjorie est convaincue que Jennie n'est pas la bonne fille pour son fils, et après une confrontation avec Jennie lorsqu'elle lui dit cela, Marjorie meurt d'une crise cardiaque. Malgré la désapprobation des deux familles, Joe et Jennie se marient (What A Lovely Day for a Wedding), un mariage observé par les fantômes malheureux de Marjorie et de la grand-mère (Wish Them Well).

A.2) Acte II

C'est la crise qui suit la dépression de 1929. Joe gagne sa vie en tant qu'assistant de son père. L'entreprise de M. Brinker a fait faillite et il vit avec le couple, qui connaît la pauvreté pour la première fois de sa vie. La pauvreté affecte plus Jennie que Joe: la nouvelle Mme Taylor n'aime pas la vie de femme au foyer pauvre (Money Isn’t Everything). Lorsqu'elle apprend que Joe a refusé une offre lucrative d'un éminent médecin de Chicago, qui est l'oncle de son ami d’université Charlie Townsend, Jennie se met d'abord en colère. Lorsqu'elle découvre que cette colère n'est pas efficace, elle le fait changer d'avis par culpabilité: s'il accepte l'offre du Dr Denby, il peut gagner l'argent nécessaire pour démarrer le petit hôpital dont rêve son père et ils auront l'argent pour élever leurs enfants correctement. (Poor Joe - Reprise).

Bien que triste de quitter le cabinet de son père, Joe accepte le poste de Bigby Denby à Chicago. En planifiant son départ de l'entreprise familiale, Joe partage avec son père ses regrets d’arrêter la poursuite des soins à ses patients. Juste avant que Joe ne parte, la voix de sa mère décédée lui dit de rester si son cœur est si lourd, et la voix de Charlie Townsend lui dit que les gens penseraient qu'il est fou de ne pas y aller. Il explique à son père qu'il accepte le poste de Jennie et s'en va.

À Chicago, Joe se retrouve bientôt à s'occuper d’hypocondriaques chroniques (Yatata, Yatata, Yatata). Obligé de satisfaire le bonheur des clients les plus rémunérateurs du cabinet, Joe doit assister à des fêtes et participer à leur vie sociale, ce qui lui laisse moins de temps pour s'occuper des patients qui pourraient en avoir réellement besoin. Dans son nouveau rôle d'épouse mondaine, Jennie aime garder Joe au courant de tous ses engagements. Charlie Townsend fait également partie des festivités, mais l'ancienne star du football s'est tournée vers la boisson. Joe lui-même devient négligent à cause de toutes ces distractions. Une erreur est commise par son infirmière, Emily, qui admire grandement le médecin que Joe pourrait être. (The Gentleman is a Dope).

Le Dr Denby félicite Joe pour ses compétences, tant médicales que sociales. Denby, vu son âge, a moins de temps pour une infirmière, Carrie Middleton, qui travaille dans son hôpital depuis 30 ans et est sortie avec lui. Mais cette dernière est impliquée dans une protestation syndicale. Denby ordonne à Emily de licencier l'infirmière la plus âgée qui travaille à l'hôpital depuis 30 ans, à la demande de Lansdale, un administrateur influent et fabricant de savon. Charlie Townsend, Joe et Emily commentent le rythme frénétique du monde de Chicago dans lequel ils vivent (Allegro).

Au fil du temps, Joe devient de plus en plus déçu par son travail dans la grande ville et pense souvent à ses patients chez lui qui, à ses yeux, méritent davantage le temps et les connaissances d'un médecin. Il apprend que Jennie a une liaison avec ce fameux Lansdale et se rend compte qu'il a cessé de l'aimer depuis longtemps, mais qu'il était trop distrait pour le voir. Alors que Joe est assis, la tête dans les mains, sa défunte mère et un chœur d'amis qu'il a laissés lui demandent de revenir (Come Home).

Joe occupe le poste de médecin en chef à l'hôpital de Chicago, en remplacement de Denby, qui est «expulsé à l'étage», à un poste de direction. Lors de l'inauguration d'un nouveau pavillon à l'hôpital, Joe a une révélation et revoit les grandes étapes de sa vie. A ce moment, Grand-mère appelle et demande à Marjorie de venir observer, un souvenir de la scène dans laquelle Joe a appris à marcher.

Joe décline publiquement son nouveau poste, décidant plutôt de retourner dans sa petite ville natale pour travailler avec son père. Accompagné d'Emily et Charlie Townsend, Joe part, laissant Jennie à Chicago (Finale: One Foot, Other Foot). Il réapprend à marcher….

Différentes versions de l'oeuvre

▶ Original Version [1947]

▶ Encores! Version [1994], Prepared for the 1994 Encores! Production

▶ DiPietro Version [2002]

Acte I

"Joseph Taylor, Jr." (Ensemble)

"I Know It Can Happen Again" (Grandma Taylor)

"One Foot, Other Foot" (Ensemble)

"A Fellow Needs a Girl" (Dr. Taylor, Marjorie Taylor)

"Freshman Dance" (Ensemble)

"A Darn Nice Campus" (Joe Taylor)

"The Purple and the Brown" (Ensemble)

"So Far" (Beulah)

"You Are Never Away" (Joe, Jenny Brinker, and ensemble)

"What a Lovely Day for a Wedding" (Ensemble)

"It May Be a Good Idea for Joe" (Charlie Townsend)

"To Have And To Hold" (Ensemble)

"Wish Them Well" (Ensemble)

Acte II

"Money Isn't Everything" (Jenny and other wives)

"Hazel Dances" (Instrumental)

"Yatata, Yatata, Yatata" (Charlie and ensemble)

"The Gentleman is a Dope" (Emily)

"Allegro" (Charlie, Joe, Emily, and ensemble)

"Come Home" (Marjorie)

Finale: "One Foot, Other Foot" (reprise) (Ensemble)

1) Genèse

1) Introduction: engagement politique

1) Introduction: engagement politique

2) Une œuvre définitivement «à part»

2) Une œuvre définitivement «à part»

3) La Theatre Guild pour la troisième et dernière fois

3) La Theatre Guild pour la troisième et dernière fois

4) Un premier acte très long à finaliser: 18 mois

4) Un premier acte très long à finaliser: 18 mois

5) Un second acte écrit dans l'urgence: 2 semaines

5) Un second acte écrit dans l'urgence: 2 semaines

2) Création

2) Try-Out à New Haven et Boston

2) Try-Out à New Haven et Boston

Version 1

Allegro (1947-09-01-Shubert Theatre-New Heaven)

Type de série: Pre-Broasway Try OutThéâtre: Shubert Theatre (New Heaven - Etats-Unis) Durée : Nombre : Première Preview : 01 September 1947

Première: 01 September 1947

Dernière: 06 September 1947Mise en scène : Agnès de Mille • Chorégraphie : Agnès de Mille • Producteur : Star(s) : Avec: Marjorie Taylor - Annamary Dickey / Dr. Joseph Taylor - William Ching / Mayor - Edward Platt / Grandma Taylor - Muriel O'Malley / Friends of Joey - Ray Harrison, Frank Westbrook / Jennie Brinker - Roberta Jonay / Principal - Robert Byrn / Mabel - Evelyn Taylor / Bicycle Boy - Stanley Simmons

Version 2

Allegro (1947-09-08-Colonial Theatre-Boston)

Type de série: Pre-Broasway Try OutThéâtre: Colonial Theatre (Boston - Etats-Unis) Durée : 3 semaines Nombre : Première Preview : 08 September 1947

Première: 08 September 1947

Dernière: 04 October 1947Mise en scène : Agnès de Mille • Chorégraphie : Agnès de Mille • Producteur : Star(s) : Avec: Marjorie Taylor - Annamary Dickey / Dr. Joseph Taylor - William Ching / Mayor - Edward Platt / Grandma Taylor - Muriel O'Malley / Friends of Joey - Ray Harrison, Frank Westbrook / Jennie Brinker - Roberta Jonay / Principal - Robert Byrn / Mabel - Evelyn Taylor / Bicycle Boy - Stanley Simmons

Version 3

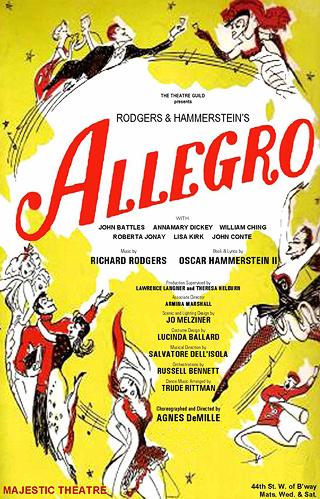

Allegro (1947-10-Majestic Theatre-Broadway)

Type de série: Original BroadwayThéâtre: Majestic Theatre (Broadway - Etats-Unis)

Durée : 9 mois Nombre : 315 représentationsPremière Preview : 10 October 1947

Première: 10 October 1947

Dernière: 10 July 1948Mise en scène : Agnès de Mille • Chorégraphie : Agnès de Mille • Producteur : Star(s) : Avec: Annamary Dickey (Marjorie Taylor), William Ching (Dr. Joseph Taylor), Edward Platt (Mayor, Minister), Muriel O’Malley (Grandma Taylor), Ray Harrison (Joey’s Friend), Frank Westbrook (Joey’s Friend), Roberta Jonay (Jennie Brinker), Robert Byrn (Principal, Biology Professor), Evelyn Taylor (Mabel), Stanley Simmons (Bicycle Boy), Harrison Muller (Georgie), Kathryn Lee (Hazel), John Conte (Charlie Townsend), John Battles (Joseph Taylor Jr.), Susan Svetlik (Miss Lipscomb, Shakespeare Student), Charles Tate (Cheer Leader), Sam Steen (Cheer Leader), Wilson Smith (Coach, Buckley), Paul Parks (Ned Brinker), David Collyer (English Professor), William McCully (Chemistry Professor), Raymond Keast (Greek Professor), Blake Ritter (Philosophy Professor), Ray Harrison (Bertram Woolhaven), Katrina Van Oss (Molly), Gloria Wills (Beulah), Julie Humphries (Millie), Sylvia Karlton (Dot), Patricia Bybell (Addie), Lawrence Fletcher (Dr. Bigby Denby), Frances Rainer (Mrs. Mulhouse), Lily Paget (Mrs. Lansdale), Bill Bradley (Jarman), Jean Houloose (Maid), Lisa Kirk (Emily), Tom Perkins (Doorman). Stephen Chase (Brooks Lansdale); Singers: Mary O’Fallon, Charlotte Howard, Lily Paget, Helen Hunter, Sylvia Karlton, Priscilla Hathaway, Gay Lawrence, Josephine Lambert, Julie Humphries, Patricia Bybell, Yolanda Renay, Devida Stewart, Nanette Vezina, Mia Stenn, Lucille Udovick, Glen Scandur, Gene Tobin, Walter Kelvin, Bernard Green, David Collyer, Joseph Caruso, Tommy Barragan, Victor Clarke, Edward Platt, Robert Reeves, Wilson Smith, Tom Perkins, James Jewell, David Poleri, Robert Neukum, Raymond Keast, Wesley Swails, Clarence Hall, Blake Ritter, Ralph Patterson, Robert Byrn, William McCully, Robert Arnold; Dancers: Jean Tachau, Evelyn Taylor, Mariane Oliphant, Patricia Gianinoto, Andrea Dowling, Jean Houloose, Therese Miele, Frances Rainer, Susan Svetlik, Ruth Ostrander, Patricia Barker, William Bradley, Daniel Buberniak, Bob Herget, John Laverty, Ralph Linn, Harrison Muller, Stanley Simmons, Charles Tate, Frank Westbrook, Ralph Williams, Sam Steen

Version 4

Allegro (1994-03-New York City Center) Encores! Concert

Type de série: ConcertThéâtre: New York City Center (Broadway - Etats-Unis) Durée : Nombre : 4 previews - Première Preview : Inconnu

Première: 02 March 1994

Dernière: 05 March 1994Mise en scène : Susan H. Schulman • Chorégraphie : Producteur : Star(s) : Avec: Carolann Page (Marjorie Taylor), John Cunningham (Dr. Joseph Taylor), Celeste Holm (Grandma Taylor), Donna Bullock (Jenny Brinker), Jonathan Hadary (Charlie Townsend), Stephen Bogardus (Joseph Taylor, Jr.), John Horton (Ned Brinker), Karen Ziemba (Beulah), Erick Devine (Dr. Bigby Denby), Christine Ebersole (Emily West)

Version 5

Allegro (2004-02-Fairview Library Theatre-Toronto)

Type de série: RevivalThéâtre: Fairview Library Theatre (Toronto - Canada) Durée : 1 semaine Nombre : Première Preview : 19 February 2004

Première: 19 February 2004

Dernière: 28 February 2004Mise en scène : ???? ???? • Chorégraphie : ???? ???? • Producteur : Star(s) :

Version 6

Allegro (2014-11-Classic Stage Theatre-Off-Broadway)

Type de série: RevivalThéâtre: Classic Stage Theatre (Broadway (Off) - Etats-Unis) Durée : 3 semaines Nombre : Première Preview : 01 November 2014

Première: 19 November 2014

Dernière: 14 December 2014Mise en scène : John Doyle • Chorégraphie : Producteur : Star(s) : Avec: George Abud (Charlie Townsend); Alma Cuervo (Grandma Taylor/Mrs. Townsend); Elizabeth A. Davis (Jenny Brinker); Claybourne Elder (Joseph Taylor, Jr.); Malcolm Gets (Joseph Taylor, Sr.); Maggie Lakis (Hazel); Paul Lincoln (Minister / Brook Lansdale); Megan Loomis (Millie / Beulah); Jane Pfitsch (Molly / Emily); Randy Redd (Dr. Bigby Denby); Ed Romanoff (Ned Brinker / Mr. Buckley); Jessica Tyler Wright (Marjorie Taylor)Commentaires : 6 nominations aux Lucille Lortel Award

Pas encore de video disponible pour ce spectacle

Allegro (1947 Original Broadway Cast recording) - 10 titres - 1947 - Durée: 00:33:37

Allegro (2008 Studio Cast) - 44 titres - 2008 - Durée: 01:35:00

Rodgers & Hammerstein Organiszation - Allegro

Rodgers & Hammerstein Organiszation - Allegro