Pas de biographie disponible.

Compositeur Musique additionelle Librettiste Parolier Metteur en scène Chorégraphe Producteur création Producteur version

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: Livret: F. C. Burnand • Production originale: 2 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Isnpiration Liste chansons

With this little work, Arthur Sullivan made his first entry into the world of comic opera. He had already completed his first operatic work during the early 1860's, but that work (The Sapphire Necklace or The False Heiress with libretto by H. F. Chorley) never reached the stage, and although the rights of publication were, at one point, assigned to the publisher, Metzler, the opera was never printed.

Genèse: The Moray Minstrels were an informal gathering of notable members of London society and the arts, including painters, actors and writers (all male), who were mostly amateur musicians. They would meet for musical evenings at Moray Lodge, in Kensington, the home of Arthur James Lewis (1824–1901), a haberdasher and silk merchant (of the firm Lewis & Allenby), who married the actress Kate Terry in 1867. The Minstrels would discuss the arts, smoke and sing part-songs and other popular music at monthly gatherings of more than 150 lovers of the arts; their conductor was John Foster. Foster, as well as the dramatist F. C. Burnand and many other members were friendly with young Arthur Sullivan, who joined the group. On one occasion in early 1865, they heard a performance of Offenbach's short two-man operetta Les deux aveugles ("The Two Blind Men"). After seeing another operetta at Moray Lodge the following winter, Burnand asked Sullivan to collaborate on a new piece to be performed for the Minstrels. Burnand adapted the libretto for this "triumviretta" from John Maddison Morton's famous farce, Box and Cox, which had premiered in London in 1847, starring J. B. Buckstone. The text follows Morton's play closely, differing in only two notable respects. First, in the play the protagonists lodge with Mrs Bouncer; in Burnand's version the character is Sergeant Bouncer. This change was necessitated by the intention of performing the piece for the all-male gathering of the Moray Minstrels. Secondly, Burnand wrote original lyrics to be set to music by the 24-year-old Sullivan. The date and venue of the first performance was much disputed, starting in 1890, in duelling letters to The World, with Burnand and Lewis each claiming to have hosted it. Andrew Lamb has concluded that the run-through at Burnand's home on 23 May 1866 was a rehearsal, followed by the first performance at Lewis's home on 26 May 1866. A printed programme for the 23 May performance later surfaced, suggesting more than a mere rehearsal, but the composer himself supported the later date, writing to The World, "I feel bound to say that Burnand's version came upon me with the freshness of a novel. My own recollection of the business is perfectly distinct". George Grove noted in his diary of 13 May that he attended a performance of Cox and Box, which Lamb takes to have been an open rehearsal; however, Foster calls the performance at Burnand's house a rehearsal. The original cast was George du Maurier as Box, Harold Power as Cox, and John Foster as Bouncer, with Sullivan himself improvising the accompaniment at the piano. Another performance at Moray Lodge took place eleven months later on 26 April 1867. This was followed by the first public performance, which was given as part of a charity benefit by the Moray Minstrels (along with Kate, Florence and Ellen Terry and others) for the widow and children of C. H. Bennett, on 11 May 1867 at the Adelphi Theatre, with du Maurier as Box, Quintin Twiss as Cox and Arthur Cecil as Bouncer, performing as an amateur under his birth name, Arthur Blunt. A review in The Times commented that Burnand had adapted Morton's libretto well, and that Sullivan's music was "full of sparking tune and real comic humour". The rest of the evening's entertainment included a musicale by the Moray Minstrels, the play A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing and Les deux aveugles. The opera was heard with a full orchestra for the first time on that occasion, with Sullivan completing the orchestration a matter of hours before the first rehearsal. The Musical World praised both author and composer, suggesting that the piece would gain success if presented professionally. It was repeated on 18 May 1867 at the Royal Gallery of Illustration in Regent Street. The critic for the magazine Fun, W. S. Gilbert, wrote of the 11 May performance: Mr. Burnand's version of Box and Cox ... is capitally written, and Mr. Sullivan's music is charming throughout. The faults of the piece, as it stands, are twain. Firstly: Mr. Burnand should have operatized the whole farce, condensing it, at the same time, into the smallest compass, consistent with an intelligible reading of the plot. ... Secondly, Mr. Sullivan's music is, in many places, of too high a class for the grotesquely absurd plot to which it is wedded. It is very funny, here and there, and grand or graceful where it is not funny; but the grand and the graceful have, we think, too large a share of the honours to themselves. The music was capitally sung by Messrs. Du Maurier, Quintin, and Blunt. At yet another charity performance, at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, on 29 July 1867, the overture was heard for the first time. The autograph full score is inscribed, Ouverture à la Triumvirette musicale 'Cox et Boxe' et 'Bouncer' composée par Arthur S. Sullivan, Paris, 23 Juillet 1867. Hotel Meurice. The duet, "Stay, Bouncer, stay!" was probably first heard in this revival. There were discussions about an 1867 professional production under the management of Thomas German Reed, but instead Reed commissioned Sullivan and Burnand to write a two-act comic opera, The Contrabandista, which was less well received. Cox and Box had its first professional production under Reed's management at the Royal Gallery of Illustration on Easter Monday, 29 March 1869, with Gilbert and Frederic Clay's No Cards preceding it on the bill. The occasion marked the professional debut of Arthur Cecil, who played Box. German Reed played Cox and F. Seymour played Bouncer. Cox and Box ran until 20 March 1870, a total of 264 performances, with a further 23 performances on tour. The production was a hit, although critics lamented the loss of Sullivan's orchestration (the Gallery of Illustration was too small for an orchestra): "The operetta loses something by the substitution... of a piano and harmonium accompaniment for the orchestral parts which Mr. Sullivan knows so well how to write; but the music is nevertheless welcome in any shape." Subsequent productions Cox and Box quickly became a Victorian staple, with additional productions in Manchester in 1869 and on tour in 1871 (conducted by Richard D'Oyly Carte, with the composer's brother Fred playing Cox), at London's Alhambra Theatre in 1871, with Fred as Cox, and at the Gaiety Theatre in 1872, 1873, and 1874 (the last of these again starring Fred as Cox and Cecil as Box), and Manchester again in 1874 (paired with The Contrabandista). There were also numerous charity performances beginning in 1867, including two at the Gaiety during the run of Thespis, and another in Switzerland in 1879 with Sullivan himself as Cox and Cecil as Box. Sullivan sometimes accompanied these performances. The cast for a performance at the Gaiety in 1880 included Cecil as Box, George Grossmith as Cox and Corney Grain as Bouncer. The first documented American production opened on 14 April 1879 at the Standard Theatre, in New York, as a curtain raiser to a "pirated" production of H.M.S. Pinafore. In an 1884 production at the Court Theatre, the piece played together with Gilbert's Dan'l Druce, Blacksmith (but later in the year with other pieces), with Richard Temple as Cox, Cecil as Box, and Furneaux Cook as Bouncer. This production was revived in 1888, with Cecil, Eric Lewis and William Lugg playing Box, Cox and Bouncer. The first D'Oyly Carte Opera Company performance of the piece was on 31 December 1894, to accompany another Sullivan–Burnand opera, The Chieftain, which had opened on 12 December at the Savoy Theatre. For this production Sullivan cut the "Sixes" duet and verses from several other numbers, and dialogue cuts were also made. Temple played Bouncer and Scott Russell was Cox. It then was played by several D'Oyly Carte touring companies in 1895 and 1896. In 1900, the piece was presented at the Coronet Theatre with Courtice Pounds as Box. In 1921, Rupert D'Oyly Carte introduced Cox and Box as a curtain raiser to The Sorcerer, with additional cuts prepared by J. M. Gordon and Harry Norris. This slimmed-down "Savoy Version" remained in the company’s repertory as curtain raiser for the shorter Savoy Operas. By the 1960s, Cox and Box was the usual companion piece to The Pirates of Penzance. It received its final D'Oyly Carte performance on 16 February 1977. Many amateur theatre companies have also staged Cox and Box – either alone or together with one of the shorter Savoy Operas. In recent years, after the rediscovery of the one-act Sullivan and B. C. Stephenson opera, The Zoo, Cox and Box has sometimes been presented as part of an evening of the three Sullivan one-act operas, sharing a bill with The Zoo and Trial by Jury.

Résumé: Sergeant Bouncer, an old soldier, has a scheme to get double rent from a single room. By day he lets it to Mr. Box (a printer who is out all night) and by night to Mr. Cox (a hatter who works all day). Whenever either of them asks any awkward questions he sings at length about his days in the militia. His plan works well until Mr. Cox is, unexpectedly, given a day's holiday and the two lodgers meet. Left alone while Bouncer sorts out another room, they discover they share more than the same bed. Cox is engaged to the widow Penelope Ann Wiggins - a fate that Box escaped by pretending to commit suicide. They try gambling Penelope Ann away until news arrives that she has been lost at sea and has left her fortune to her 'intended'. They then both try to claim her for themselves. Another letter arrives - she has been found and will arrive any minute. Now they both try to disclaim her! However, she doesn't appear personally, instead leaving a letter to inform them that she intends to marry a Mr. Knox! Relieved, Cox and Box swear eternal friendship and discover, curiously enough, that they are long-lost brothers…

Création: 11/5/1867 - Adelphi Theatre (Londres) - représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 1 version mentionnée

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

Il s’agit de la première collaboration de Gilbert et Sullivan et a été conçue comme un divertissement de Noël pour le Gaiety Theatre de John Hollingshead où s'est déroulé la première représentation, le 26 décembre 1871, et a connu 63 représentations. Bien qu'il ait souvent été décrit comme un échec, il a accueilli plus de spectateurs que les autres spectacles de Noël cette saison-là.

Genèse:

1) Genèse

Le Gaiety Theatre (1864-1939, démoli en 1956) à l'extrémité est du strand

«The Illustrated London News» du 20 octobre 1866

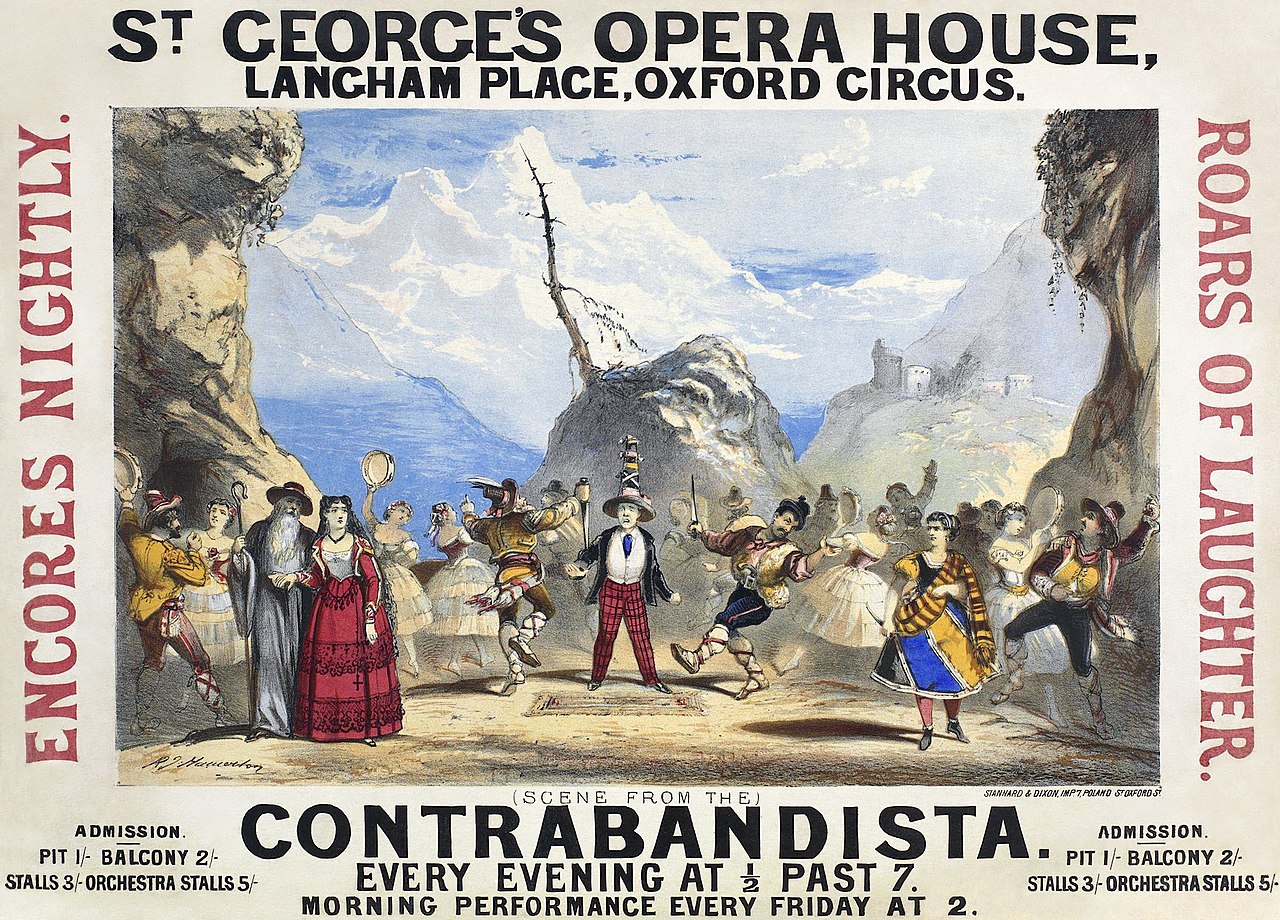

Affiche de «The Contrabandista»

2) Composition

Gilbert a eu un automne chargé. Sa pièce On Guard a connu un échec au Court Theatre, ouvrant le 28 octobre 1871, alors que Pygmalion and Galatea, sont plus grand succès théâtral, a été créée le 9 décembre 1871, quelques jours seulement avant le début des répétitions de Thespis (). Sullivan, lui, avait plus de temps libre après avoir composé de ka musique de scène pour The Merchant of Venice de Shakespeare créée à Manchester le 9 septembre 1871. Gilbert et Sullivan se souviennent tous deux que Thespis () a été écrit à la hâte. Sullivan se borne à déclarer que «la musique et le livret ont été écrits très rapidement». Dans son autobiographie de 1883, Gilbert est plus clair et acerbe:Peu de temps après la production de Pygmalion and Galatea, j'ai écrit le premier d'une longue série de livrets, en collaboration avec M. Arthur Sullivan. Cela s'appelait Thespis (). L'écriture a mis moins de trois semaines et a été créée au Gaiety Theatre après une semaine de répétition. Il a tenu l'affiche 84 soirs, mais c'était un oeuvre grossière et inefficace, comme on pouvait s'y attendre, compte tenu des circonstances de sa composition rapide.

Gilbert S. SUllivan - 1883

En 1902, les souvenirs de Gilbert sont légèrement différents:

Je peux affirmer que Thespis () n'a en aucun cas été un échec, même s'il n'a pas connu de succès considérable. Je crois qu'il s'est joué environ 70 soirs, ce qui était assez convenable à l'époque. La pièce a été produite sous la pression d'une immense hâte. Tout a été imaginé, écrit, composé, répété et produit en cinq semaines.

Gilbert S. SUllivan - 1902

L'estimation de Gilbert sur 5 semaines de création est en conflit avec d'autres faits apparemment incontestables. Le neveu de Sullivan, Herbert Sullivan, a écrit que le livret existait déjà avant que son oncle ne s'implique dans le projet: «Gilbert a montré à Hollingshead le livret d'un opéra Extravaganza Thespis, et Hollingshead l'a immédiatement envoyé à Sullivan pour qu'il en compose la musique.» Gilbert créait généralement une ébauche de ses livrets quelques mois avant une production, mais n'écrivait pas un livret fini avant d'avoir un engagement ferme pour le produire. À tout le moins, une «ébauche de l'intrigue» devait exister au 30 octobre 1871, à la lumière d'une lettre à cette date de l'agent de Gilbert à R.M. Field directeur du Boston Museum Theatre (important théâtre de Boston), qui se lit comme suit :

À Noël sera produit au Gaiety Theatre, un nouvel et original Opera Bouffe en anglais par WS Gilbert dont Arthur Sullivan compose la nouvelle musique. On s'attend à ce que ce soit une événement - et le but de ma présente lettre est - premièrement - de vous envoyer (ce jour) une ébauche de la pièce pour votre propre lecture, et deuxièmement de vous demander - si vous vous en souciez et si vous le souhaitez de faire en sorte que la pièce soit dûment protégée - en vue de sa vente dans tous les endroits possibles aux États-Unis. Messieurs Gibert et Sullivan travaillent actuellement d'arrache-pied sur cette pièce.

"The First Night - Gilbert and Sullivan" - Allen Reginald - 1958

Gilbert a en fait conclu un accord avec le directeur du Boston Museum, R.M. Field, et le premier livret publié conseillait: «Attention aux pirates américains. — Les droits d'auteur des dialogues et de la musique de cette pièce, pour les États-Unis et le Canada, ont été attribués à M. Field, du Boston Museum, par accord en date du 7 décembre 1871.» Toutefois, si R.M. Field a monté l'œuvre, la production n'a pas été suivie de paiement de droits... L'inquiétude de Gilbert concernant les pirates américains du droit d'auteur préfigurait les difficultés que lui et Sullivan rencontreraient plus tard avec les productions «piratées» non autorisées du HMS Pinafore (), de The Mikado () et de leurs autres œuvres populaires. En tout cas, le livret a été «publié et diffusé» à Londres à la mi-décembre 1871.

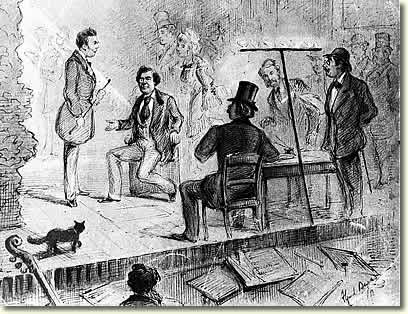

«Thespis» en répétitions au Gaiety Theatre en décembre 1871

Gilbert est visible derrière le «tube de gaz en T» qui sert d'éclairage de répétitions

© Dessin à la plume et à l'encre d'Alfred Bryan

Jusqu'à ce que Gilbert prenne les choses en main, les chœurs étaient prsque toujours réduit à de la figuration, n'étaient pratiquement rien d'autre qu'une partie du décor. C'est dans Thespis () que Gilbert a commencé à mettre en œuvre sa détermination exprimée pour que le chœur joue le rôle qui lui revient dans la représentation. À l’heure actuelle, il semble difficile de comprendre que l’idée que le chœur soit autre chose qu’une sorte de public sur scène, ait été à cette époque une formidable nouveauté. En raison de cette innovation, certains incidents lors des répétitions de Thespis () furent plutôt amusants. Je me souviens qu'un jour, l'un des des premiers rôles féminins s'est indignée et a dit: «Vraiment, M. Gilbert, pourquoi devrais-je rester ici? Je ne suis pas une chorus-girl!» Ce à quoi Gilbert répondit sèchement: «Non, madame, votre voix n’est pas assez forte. Ou vous le seriez sans doute.»

4)Réception de l'oeuvre

Scène de «Thespis» au Gaiety Theatre à la création

Le soir de la première, il était évident que le spectacle n'avait pas été assez répété, comme l'ont noté plusieurs critiques, et l'œuvre avait également manifestement besoin de subir quelques coupures... La direction du Gaiety Theatre avait conseillé que les calèches soiet présentes à 23h pour récupérer les spectateurs chics. Mais, passé minuit, Thespis () était toujours en cours. The Observer a déclaré que «le jeu des acteurs et l'oeuvre devront être retravaillées avant de pouvoir être équitablement critiqués... L'opéra n'était pas prêt». Le Daily Telegraph a suggéré qu'«il est plus honnête, pour de nombreuses raisons, de considérer la représentation d'hier soir comme une répétition générale complète... Quand le spectacle se terminera à l'heure normale du Gaiety Theatre, et qu'il aura été répété avec énergie, on trouvera peu de divertissements plus heureux que celui-ci.» Certains critiques n'ont pas pu détecter, vu le manque de répétition, les qualités de l'oeuvre, une fois que tout serait finalisé. Le Hornet a sous-titré sa critique: «Thespis, ou les dieux devenus vieux et lassants!» Le Morning Advertiser a parlé d'«une intrigue morne et fastidieuse en deux actes... grotesque sans esprit, et la musique mince sans vivacité... cependant, pas entièrement dénuée de mélodie... Le rideau tombant devant un public bâillant et fatigué.» Mais d'autres ont trouvé beaucoup à admirer dans le travail, malgré la mauvaise performance de la soirée d'ouverture. L'Illustrated Times a écrit :

Il est terriblement grave pour Mr. W.S. Gilbert et Arthur Sullivan, les co-auteurs de Thespis () , que leur travail ait été présenté dans un état aussi rudimentaire et insatisfaisant. Thespis () a de nombreux mérites: les mérites de la valeur littéraire, les mérites du plaisir, les mérites de l’écriture de chansons, ... Il mérite de réussir; mais la direction du théâtre a paralysé une bonne pièce par l'insuffisance des répétitions et par le manque de polissage et d'assurance requis sans lesquels ces opéras joyeux sont inutiles. Je dois cependant préciser que Thespis () vaut vraiment le détour; et quand il aura été corrigé et attirera le vrai public du Gaiety, il tiendra bon courageusement. Il est vraiment dommage qu'une pièce aussi riche en humour et si délicate en musique ait été montée pour l'édification du public d'une Boxing-Night*. Sauf erreur grave, et malgré les sifflements de Boxing-Night, les ballades et l'esprit de M. Gilbert et les jolies mélodies de M. Arthur Sullivan permettront à Thespis () de dépasser cette épreuve et en feront, comme elle mérite de l'être, la pièce la plus louable de la saison de Noël.

"Thespis – A Gilbert & Sullivan Enigma" - Terence Rees - 1964

* En Angleterre le 26 décembre est appelé le «Boxing Day»

Clement Scott, écrivant dans le Daily Telegraph, a eu une réaction plutôt favorable :

Il est possible qu'un public en vacances soit peu enclin à se plonger dans les mystères de la mythologie païenne et ne se soucie pas d'exercer l'intelligence requise pour démêler une intrigue amusante et en aucun cas complexe. Il est cependant certain que l'accueil par le punlic de Thespis () n’a pas été aussi cordial qu’on aurait pu s’y attendre. L'histoire, écrite par Mr. W.S. Gilbert de la plus vivante des manières, est si originale et la musique composée par M. Arthur Sullivan si jolie et fascinante, que nous sommes enclins à être déçus lorsque nous trouvons les applaudissements faibles et les rires à peine spontanés. Et surtout que le rideau tombe non sans sifflets de désapprobation. Un tel sort n’était certainement pas mérité, et le verdict d’hier soir ne peut être considéré comme définitif. Thespis () est trop beau pour être mis de côté et écarté de cette façon: et nous prévoyons qu'une réduction judicieuse et de nouvelles répétitions nous permettront bientôt de raconter une histoire très différente.

"The First Night - Gilbert and Sullivan" - Allen Reginald - 1958

The Observer a commenté :

Représentations ultérieures De nombreux auteurs du début du XXème siècle ont perpétué le mythe selon lequel Thespis () n'était resté qu'un mois à l'affiche et pouvait être considéré comme un échec. En fait, il est resté ouvert jusqu'au 8 mars 1872. Sur les neuf pantomimes londoniennes créées pendant les fêtes de Noël de 1871, cinq ont fermé avant Thespis (). De par leur nature, les pantomimes ne se prêtaient pas à de longues séries, et les neuf avaient fermé fin mars. De plus, le Gaiety Theatre n'accueillait normalement des productions que pendant deux ou trois semaines; le parcours de Thespis () fut en fait extraordinaire pour le théâtre.

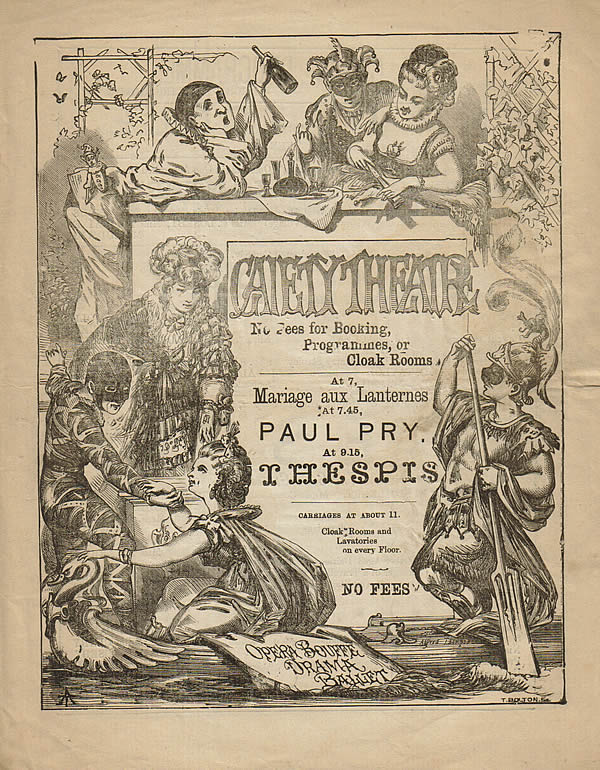

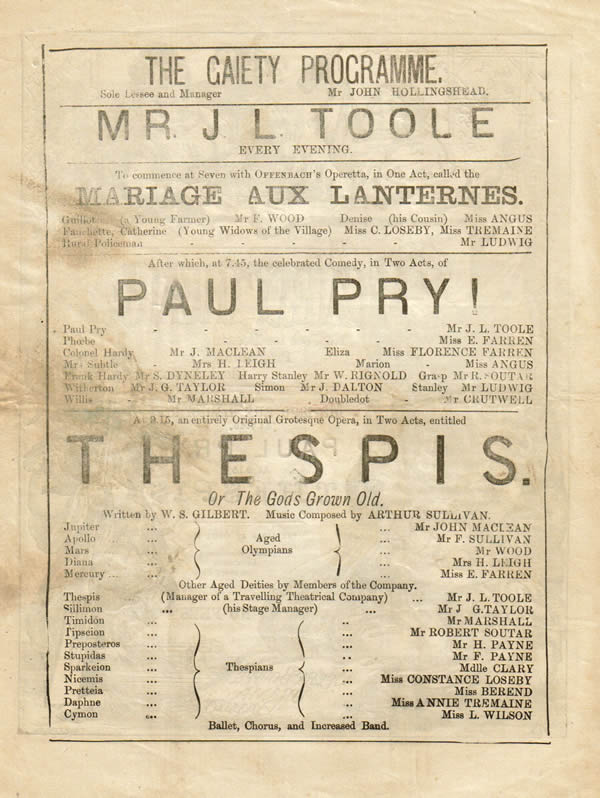

Programme issu de la production originale de «Thespis» au Gaiety Theatre,

joué avec «Mariage aux Lanternes» et «Paul Pry»

Programme issu de la production originale de «Thespis» au Gaiety Theatre,

joué avec «Mariage aux Lanternes» et «Paul Pry»

Mlle. Clary, la créatrice du rôle de Sparkion dans «Thespis»

Ils semblent très impatients d'obtenir notre accord et veulent que je leur donne des conditions précises. Bien sûr, je ne peux pas répondre à ta place, mais ils m'ont tellement pressé de leur donner une idée de ce que seraient nos conditions que j'ai suggéré que nous pourrions éventuellement être disposés à accepter deux guinées par soir chacun avec une garantie de 100 soirs minimum. Est-ce que cela correspond à ton point de vue, et si oui, pourrons-nous le faire à temps? Je vais réécrire une partie considérable du dialogue.

Le projet de reprise fut mentionné dans plusieurs autres courriers tout au long de l'automne 1875, jusqu'à ce que le 23 novembre Gilbert écrive: «Je n'ai plus entendu parler de Thespis (). Il est étonnant de voir avec quelle rapidité ces capitalistes s'assèchent sous l'influence magique des mots «cash down».» Vingt ans plus tard, en 1895, alors que Richard D'Oyly Carte luttait pour retrouver le succès au Savoy Theatre, il proposa une fois de plus une reprise de Thespis (), mais l'idée n'aboutit pas. Et depuis 1897, on n'a aucune idée de l'endroit où se trouve les partitions de Thespis (). Et de très nombreux spécialistes et amateurs les ont recherchées parmi de nombreuses collections existantes. À l'exception de deux chansons et de quelques musiques de ballet, les partitions sont aujourd'hui perdues!!!

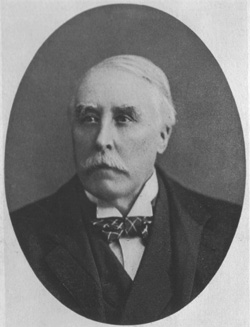

John Hollingshead en 1895

Résumé: Les dieux de l'Olympe sont vieux et fatigués et décident de quitter le Mont Olympe et de prendre des vacances. Pendant ce temps, une troupe d'acteurs itinérants prennent leur place.

Création: 26/12/1871 - Gaiety Theatre (Londres) - 63 représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 12 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

La deuxième collaboration de Gilbert et Sullivan, qui est aussi leur premier "triomphe" et leur seul opéra-comique en un acte.

Genèse: Before Trial by Jury, W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan had collaborated on one previous opera, Thespis; or, The Gods Grown Old, in 1871. Although reasonably successful, it was a Christmas entertainment, and such works were not expected to endure. Between Thespis and Trial by Jury, Gilbert and Sullivan did not collaborate on any further operas, and each man separately produced works that further built his reputation in his own field. Gilbert wrote several short stories, edited the second volume of his comic Bab Ballads, and created a dozen theatrical works, including Happy Arcadia in 1872; The Wicked World, The Happy Land and The Realm of Joy in 1873; Charity, Topsyturveydom and Sweethearts in 1874. At the same time, Sullivan wrote various pieces of religious music, including the Festival Te Deum (1872) and an oratorio, The Light of the World (1873), and edited Church Hymns, with Tunes (1874), which included 45 of his own hymns and arrangements. Two of his most famous hymn tunes from this period are settings of "Onward, Christian Soldiers" and "Nearer, my God, to Thee" (both in 1872). He also wrote a suite of incidental music to The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874) and many parlour ballads and other songs, including three in 1874–75 with words by Gilbert: "The Distant Shore", "Sweethearts" (inspired by Gilbert's play) and "The Love that Loves Me Not".

Genesis of the opera

The genesis of Trial by Jury was in 1868, when Gilbert wrote a single-page illustrated comic piece for the magazine Fun entitled Trial by Jury: An Operetta. Drawing on Gilbert's training and brief practice as a barrister, it detailed a "breach of promise" trial going awry, in the process spoofing the law, lawyers and the legal system. (In the Victorian era, a man could be required to pay compensation should he fail to marry a woman to whom he was engaged.) The outline of this story was followed in the later opera, and two of its numbers appeared in nearly their final form in Fun. The skit, however, ended abruptly: the moment the attractive plaintiff stepped into the witness box, the judge leapt into her arms and vowed to marry her, whereas in the opera, the case is allowed to proceed further before this conclusion is reached. In 1873, the opera manager and composer Carl Rosa asked Gilbert for a piece to use as part of a season of English opera that Rosa planned to present at the Drury Lane Theatre; Rosa was to write or commission the music. Gilbert expanded Trial into a one-act libretto. Rosa's wife, Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa, a childhood friend of Gilbert's, died after an illness in 1874, and Rosa dropped the project. Later in the same year, Gilbert offered the libretto to the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte, but Carte knew of no composer available to set it to music. Meanwhile, Sullivan may have been considering a return to light opera: Cox and Box, his first comic opera, had received a London revival (co-starring his brother, Fred Sullivan) in September 1874. In November, Sullivan travelled to Paris and contacted Albert Millaud, one of the librettists for Jacques Offenbach's operettas. However, he returned to London empty-handed and worked on incidental music for the Gaiety Theatre's production of The Merry Wives of Windsor. By early 1875, Carte was managing Selina Dolaro's Royalty Theatre, and he needed a short opera to be played as an afterpiece to Offenbach's La Périchole, which was to open on 30 January (with Fred Sullivan in the cast), in which Dolaro starred. Carte had asked Sullivan to compose something for the theatre and advertised in The Times in late January: "In Preparation, a New Comic Opera composed expressly for this theatre by Mr. Arthur Sullivan in which Madame Dolaro and Nellie Bromley will appear." But around the same time, Carte also remembered Gilbert's Trial by Jury and knew that Gilbert had worked with Sullivan to create Thespis. He suggested to Gilbert that Sullivan was the man to write the music for Trial. Gilbert finally called on Sullivan and read the libretto to him on 20 February 1875. Sullivan was enthusiastic, later recalling, "[Gilbert] read it through ... in the manner of a man considerably disappointed with what he had written. As soon as he had come to the last word, he closed up the manuscript violently, apparently unconscious of the fact that he had achieved his purpose so far as I was concerned, inasmuch as I was screaming with laughter the whole time." Trial by Jury, described as "A Novel and Original Dramatic Cantata" in the original promotional material, was composed and rehearsed in a matter of weeks.Production and aftermath

The result of Gilbert and Sullivan's collaboration was a witty, tuneful and very "English" piece, in contrast to the bawdy burlesques and adaptations of French operettas that dominated the London musical stage at that time. A programme cover for the Royalty Theatre printed in black and blue with engraved illustrations and decorations. There is a large illustration of the main attraction, La Périchole, but caricatures of Gilbert and Sullivan as cherubs frame a portrait of Selina Dolaro. Initially, Trial by Jury, which runs only 30 minutes or so, was played last on a triple bill, on which the main attraction, La Périchole (starring Dolaro as the title character, Fred Sullivan as Don Andres and Walter H. Fisher as Piquillo), was preceded by the one-act farce Cryptoconchoidsyphonostomata. The latter was immediately replaced by a series of other curtain raisers. The composer conducted the first night's performance, and the theatre's music director, B. Simmons, conducted thereafter. The composer's brother, Fred Sullivan, starred as the Learned Judge, with Nellie Bromley as the Plaintiff. One of the choristers in Trial by Jury, W. S. Penley, was promoted in November 1875 to the small part of the Foreman of the Jury and made a strong impact on audiences with his amusing facial expressions and gestures. In March 1876, he temporarily replaced Fred Sullivan as the Judge, when Fred's health declined from tuberculosis. With this start, Penley went on to a successful career as comic actor, culminating with the lead role in the record-breaking original production of Charley's Aunt. Fred Sullivan died in January 1877. Jacques Offenbach's works were then at the height of their popularity in Britain, but Trial by Jury proved even more popular than La Périchole, becoming an unexpected hit. Trial by Jury drew crowds and continued to run after La Périchole closed. While the Royalty Theatre closed for the summer in 1875, Dolaro immediately took Trial on tour in England and Ireland. The piece resumed at the Royalty later in 1875 and was revived for additional London seasons in 1876 at the Opera Comique and in 1877 at the Strand Theatre. Trial by Jury soon became the most desirable supporting piece for any London production, and, outside London, the major British theatrical touring companies had added it to their repertoire by about 1877. The original production was given a world tour by the Opera Comique's assistant manager Emily Soldene, which travelled as far as Australia. Unauthorised "pirate" productions quickly sprang up in America, taking advantage of the fact that American courts did not enforce foreign copyrights. It also became popular as part of the Victorian tradition of "benefit concerts", where the theatrical community came together to raise money for actors and actresses down on their luck or retiring. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued to play the work for a century, licensing the piece to amateur and foreign professional companies, such as the J. C. Williamson Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company. Since the copyrights to Gilbert and Sullivan works ran out in 1961, the piece has been available to theatre companies around the world free of royalties. The work's enduring popularity since 1875 makes it, according to theatrical scholar Kurt Gänzl, "probably the most successful British one-act operetta of all time". The success of Trial by Jury spurred several attempts to reunite Gilbert and Sullivan, but difficulties arose. Plans for a collaboration for Carl Rosa in 1875 fell through because Gilbert was too busy with other projects, and an attempted Christmas 1875 revival of Thespis by Richard D'Oyly Carte failed when the financiers backed out. Gilbert and Sullivan continued their separate careers, though both continued writing light opera, among other projects: Sullivan's next light opera, The Zoo, opened while Trial by Jury was still playing, in June 1875; and Gilbert's Eyes and No Eyes premiered a month later, followed by Princess Toto in 1876. Gilbert and Sullivan were not reunited until The Sorcerer in 1877.Résumé: Edwin a demandé Angelina en mariage, mais aujourd'hui, il ne veut plus l'épouser. Elle l'attaque en justice pour "rupture de promesse". Nous allons donc assister à ce procès où chacun des deux jeunes va tout faire pour influer sur le niveau des dommages et intérêts. Et où surtout où va se rendre compte à quel point un procès peut ne pas être équitable…

Création: 25/3/1875 - Royalty Theatre (Londres) - 131 représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 2 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse

Après le succès précoce et retentissant de leur opéra en un acte "Trial By Jury" en 1875, Gilbert et Sullivan, et leur producteur Richard D'Oyly Carte, décidèrent de produire une œuvre plus longue. Gilbert a retravaillé et allongé un de ses écrits antérieurs (An Elixir of Love) basé sur un thème d'opéra pour créer une intrigue autour d'un philtre d'amour magique qui ferait tomber tout le monde amoureux, mais du mauvais partenaire. "The Sorcerer" a été créé à l'Opéra Comique de Londres, un charmant petit théâtre du Strand, le 17 novembre 1877. La série originale de la pièce a duré 175 représentations, un succès suffisant pour encourager Gilbert & Sullivan à continuer à collaborer, ce qui a conduit à leur pièce suivante, le HMS Pinafore.

Genèse: In 1871, W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan had written Thespis, an extravaganza for the Gaiety Theatre's holiday season that did not lead immediately to any further collaboration. Three years later, in 1875, talent agent and producer Richard D'Oyly Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre, and he needed a short opera to be played as an afterpiece to Jacques Offenbach's La Périchole. Carte was able to bring Gilbert and Sullivan together again to write the one-act piece, called Trial by Jury, which became a surprise hit. The piece was witty, tuneful and very "English", in contrast to the bawdy burlesques and adaptations of French operettas that dominated the London musical stage at that time. Trial by Jury proved even more popular than La Périchole,[6] becoming an unexpected hit, touring extensively and enjoying revivals and a world tour. After the success of Trial by Jury, several producers attempted to reunite Gilbert and Sullivan, but difficulties arose. Plans for a collaboration for Carl Rosa in 1875 fell through because Gilbert was too busy with other projects, and an attempted Christmas 1875 revival of Thespis by Richard D'Oyly Carte failed when the financiers backed out. Gilbert and Sullivan continued their separate careers, though both continued writing light opera. Finally, in 1877, Carte organised a syndicate of four financiers and formed the Comedy Opera Company, capable of producing a full-length work. By July 1877, Gilbert and Sullivan were under contract to produce a two-act opera. Gilbert expanded on his own short story that he had written the previous year for The Graphic, "An Elixir of Love," creating a plot about a magic love potion that – as often occurs in opera – causes everyone to fall in love with the wrong partner. Now backed by a company dedicated to their work, Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte were able to select their own cast, instead of using the players under contract to the theatre where the work was produced, as had been the case with their earlier works. They chose talented actors, most of whom were not well-known stars; and so did not command high fees, and whom they felt they could mould to their own style. Then, they tailored their work to the particular abilities of these performers. Carte approached Mrs Howard Paul to play the role of Lady Sangazure in the new opera. Mr and Mrs Howard Paul had operated a small touring company booked by Carte's agency for many years, but the couple had recently separated. She conditioned her acceptance of the part on the casting of her 24-year-old protege, Rutland Barrington. When Barrington auditioned before W. S. Gilbert, the young actor questioned his own suitability for comic opera, but Gilbert, who required that his actors play their sometimes-absurd lines in all earnestness, explained the casting choice: "He's a staid, solid swine, and that's what I want." Barrington was given the role of Dr Daly, the vicar, which was his first starring role on the London stage. For the character role of Mrs. Partlet, they chose Harriett Everard, an actress who had worked with Gilbert before. Carte's agency supplied additional singers, including Alice May (Aline), Giulia Warwick (Constance), and Richard Temple (Sir Marmaduke). Finally, in early November 1877, the last role, that of the title character, John Wellington Wells, was filled by comedian George Grossmith. Grossmith had appeared in charity performances of Trial by Jury, where both Sullivan and Gilbert had seen him (indeed, Gilbert had directed one such performance, in which Grossmith played the judge), and Gilbert had earlier commented favourably on his performance in Tom Robertson's Society at the Gallery of Illustration. After singing for Sullivan, upon meeting Gilbert, Grossmith wondered aloud if the role shouldn't be played by "a fine man with a fine voice". Gilbert replied, "No, that is just what we don't want." The Sorcerer was not the only piece on which either Gilbert or Sullivan were working at that time. Gilbert was completing Engaged, a "farcical comedy", which opened on 3 October 1877. He also was sorting out the problems with The Ne'er-do-Weel, a piece he wrote for Edward Sothern. Meanwhile, Sullivan was writing the incidental music to Henry VIII; only after its premiere on 28 August did he begin working on The Sorcerer. The opening was originally scheduled for 1 November 1877; however, the first rehearsals took place on 27 October, and the part of J. W. Wells was filled only by that time. The Sorcerer finally opened at Opera Comique on 17 November 1877.

Résumé: Le riche mais peu intelligent Alexis a une vision: la joie du mariage fera disparaître tout malheur terrestre. Appliquant à lui-même ce qu’il a prêché, Alexis s'est récemment fiancé à la belle Aline. Mais lors de sa cérémonie de mariage, il veut généraliser à tous sa conviction: apporter la joie du mariage à toute la ville. Pour y parvenir, il invite le patron de J.W. Wells & Co., Family Sorcerers, à préparer un philtre d'amour. Cela a un effet immédiat: tout le monde dans le village tombe amoureux de la première personne qu'il voit. Mais cela aboutit à créer des couples comiquement dépareillés. En fin de compte, Wells doit sacrifier sa vie pour briser le charme.

Création: 17/11/1877 - Opera Comique (Londres) - 175 représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: W.S. Gilbert • Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 5 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

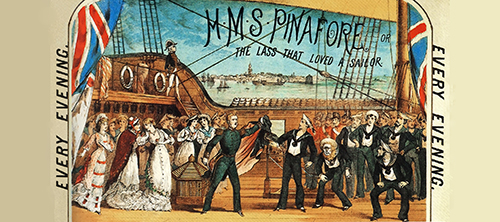

La quatrième collaboration entre Gilbert & Sullivan fut leur premier grand succès: "HMS Pinafore" (ou "La fille qui aimait un marin"). Il a ouvert ses portes le 25 mai 1878 à l'Opéra Comique où il s'est joué pour une très longue série de 571 représentations. Des tournées ont répandu sa popularité dans toute la Grande-Bretagne et en Amérique, de nombreuses compagnies ont "piraté" l'œuvre en mettant en scène des productions sans le consentement des auteurs et sans leur payer de droits d'auteurs. Gilbert, Sullivan et Carte ont tenté de battre les "pirates" en montant leur propre production à New York. Aujourd'hui, "HMS Pinafore" reste l'un des opéras de Gilbert et Sullivan les plus populaires.

Genèse: Pinafore ouvrit le 25 mai 1878 à l'Opera Comique, sous la direction de Sullivan, devant un public enthousiaste. Cependant, la pièce souffrit rapidement de faibles ventes de ticket, imputées en général à une vague de chaud qui rendit les lieux particulièrement inconfortables, puisqu'ils étaient éclairés au gaz et mal ventilés. L'historien Michael Ainger remet cette explication en question, au moins partiellement, en expliquant que les vagues de chauds de l'été 1878 étaient brèves et passagères. Quoi qu'il en soit, Sullivan écrit à sa mère à la mi-août qu'une météo plus douce était arrivée, ce qui était bon pour la représentation[39]. Dans le même temps, les quatre partenaires de la société Comedy-Opera perdirent confiance dans la viabilité de l'opéra et affichèrent des avis de fermeture[39],[40]. Carte fit connaître la pièce au public en présentant un concert lors de la matinée du 6 juillet 1878 dans l'imposant Crystal Palace. À la fin août 1878, Sullivan utilisa l'une des musiques de Pinafore, arrangée par son assistant Hamilton Clarke, durant plusieurs concerts-promenades à succès à Covent Garden, qui suscitèrent l'intérêt du public et stimulèrent les ventes de ticket. En septembre, Pinafore jouait devant des salles combles à l'Opera Comique. Les partitions au piano se vendirent à 10 000 exemplaires et Carte envoya bientôt deux troupes supplémentaires en tournée dans les provinces. Carte, Gilbert et Sullivan avaient à présent les moyens financiers de produire eux-mêmes les spectacles, sans recourir à des bailleurs de fond. Carte persuada l'auteur et le composa qu'un partenariat en affaire entre eux trois serait à leur avantage, et ils tramèrent un plan afin de se séparer des directeurs de la société Comedy-Opera. Le contrat entre Gilbert et Sullivan et la société donnait à cette dernière les droits de présenter Pinafore pour une série. L'Opera Comique fut obligé de fermer pour réparation dans les canalisations et les égouts de Noël 1878 à la fin de janvier 1879 : Gilbert, Sullivan et Carte considérèrent que cette fermeture terminait la série de représentations et, par conséquent, mirent fin aux droits de la société. Carte fut particulièrement clair en prenant un congé personnel de six mois vis-à-vis du théâtre, commençant le 1er février, la date de la réouverture lorsque Pinafore revint à l'affiche. À la fin des six mois, Carte prévoyaient d'annoncer à la société Comedy-Opera que ses droits sur la pièce et le théâtre étaient terminés. Entre temps, de nombreuses versions « pirates » du Pinafore commencèrent à être joués aux États-Unis avec un grand succès, commençant avec une production à Boston qui ouvrit le 25 novembre 1878. Pinafore devint une source de citations dans les discussions des deux côtés de l'Atlantique, tels que : "Quoi, jamais ?" "Non, jamais !" "Quoi, jamais ?" "Oh, pratiquement jamais !" Après la reprise des opérations à l'Opera Comique en février 1879, l'opéra recommença également ses tournées en avril, avec deux troupes s'entrecroisant dans les provinces britanniques, Sir Joseph étant interprété dans une troupe par Richard Mansfield, et dans l'autre par W. S. Penley. Espérant prendre sa part dans les profits faits aux États-Unis avec Pinafore, Carte partit en juin pour New York afin de mettre en place une production « authentique » qui serait préparée personnellement par l'auteur et le compositeur. Il s'organisa pour louer un théâtre et fit passer des auditions pour les membres du chœur de la production américaine de Pinafore, ainsi que d'un nouvel opéra de Gilbert et Sullivan dont la première devait avoir lieu à New York, et également pour des tournées de The Sorcerer. Sullivan, ainsi que planifié avec Carte et Gilbert, notifia les partenaires de la société Comedy-Opera au début de juillet 1879 que lui, Gilbert et Carte, ne renouvelleront pas le contrat pour produire Pinafore avec la société, et qu'il retirerait sa muqieu de la société le 31 juillet. En retour, la société fit savoir qu'il comptait produire Pinafore à un autre théâtre et entreprit une action en justice. De plus, elle offrit à la troupe de Londres et aux autres plus d'argent pour jouer dans leur production. Bien que quelques choristes acceptèrent l'offre, le seul interprète de premier plan qui s'y joignit fut Mr Dymott. La société engagea l'Imperial Theatre mais n'avait pas de décors : ils envoyèrent donc, le 31 juillet, une bande de voyous pour s'emparer des décors et des accessoires pendant le deuxième acte de la représentation du soir à l'Opera Comique. Gilbert n'était pas là, et Sullivan se remettait d'une opération de calcul rénal. Les machinistes et d'autres membres de l'équipe réussirent à éviter ces attaquants en coulisse et à protéger les décors, bien que le directeur Richard Barker et d'autres furent blessés. L'équipe continua la représentation jusqu'à ce que quelqu'un hurle « au feu ! » George Grossmith, jouant Sir Joseph, vint devant le rideau pour calmer le public paniqué. La police arriva pour restaurer l'ordre et la pièce put reprendre. Gilbert porta plainte pour empêcher la société Comedy-Opera de mettre en scène la production rivale du H.M.S. Pinafore. La cour autorisa la production à continuer à l'Imperial, où Pauline Rita incarna Josephine, commençant le 1er août 1879. La production fut transférée à l'Olympic Theatre en septembre, mais elle n'était pas aussi populaire que la production de D'Oyly Carte et fut retirée après 91 représentations. Le problème juridique fut éventuellement réglé devant la cour lorsqu'un juge trancha en faveur de Carte, deux ans plus tard.

Résumé: L'histoire se déroule à bord du navire britannique HMS Pinafore. Josephine, la fille du capitaine, est amoureuse d'un marin de classe populaire, Ralph Rackstraw, alors que son père a l'intention qu'elle épouse sir Joseph Porter, ministre de la Marine. Elle se conforme tout d'abord aux souhaits de son père, mais le plaidoyer de sir Joseph sur l'égalité entre les hommes encourage Ralph et Josephine à remettre en question le poids des couches sociales. Ils se déclarèrent leur amour puis finissent par planifier de s'enfuir pour se marier. Le capitaine découvre ce plan mais, comme dans de nombreux opéras de Gilbert et Sullivan, une révélation surprise renverse le cours des choses vers la fin de l'histoire.

Création: 25/5/1878 - Opera Comique (Londres) - représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: W.S. Gilbert • Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 7 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Commentaire Génèse Liste chansons

Après le succès sensationnel de "HMS Pinafore", de nombreuses compagnies de spectacle américaines avaient présenté des versions non autorisées de cet opéra. Gilbert, Sullivan et Carte ont décidé d'éviter que cela ne se reproduiseavec leur nouvelle création, "Les Pirates de Penzance", en en présentant les versions officielles simultanément en Angleterre et en Amérique. L'opéra fut créé le 31 décembre 1879 au Fifth Avenue Theatre à New York sous la direction de Sullivan, mais une seule représentation avait été donnée la veille au Royal Bijou Theatre, Paignton, Angleterre, pour garantir le droit d'auteur britannique. Enfin, l'opéra a ouvert ses portes le 3 avril 1880, à l'Opéra Comique de Londres, où il s'est joué pour 363 représentations, ayant connu un succès parallèle pendant plus de trois mois à New York.

Genèse: The Pirates of Penzance was the only Gilbert and Sullivan opera to have its official premiere in the United States. At the time, American law offered no copyright protection to foreigners. After their previous opera, H.M.S. Pinafore, was a hit in London, over a hundred American companies quickly mounted unauthorised productions, often taking considerable liberties with the text and paying no royalties to the creators. Gilbert and Sullivan hoped to forestall further "copyright piracy" by mounting the first production of their next opera in America, before others could copy it, and by delaying publication of the score and libretto. They succeeded in keeping for themselves the direct profits of the first production of the opera by opening the production themselves on Broadway, prior to the London production. They also operated U.S. touring companies. However, Gilbert, Sullivan, and their producer, Richard D'Oyly Carte, failed in their efforts over the next decade to control the American performance copyrights over their operas. Genesis After the success of Pinafore, Gilbert was eager to get started on the next opera, and he began working on the libretto in December 1878. He re-used several elements of his 1870 one-act piece, Our Island Home, which had introduced a pirate "chief", Captain Bang. Bang was mistakenly apprenticed to a pirate band as a child by his deaf nursemaid. Also, Bang, like Frederic, had never seen a woman before and was affected by a keen sense of duty, as an apprenticed pirate, until the passage of his twenty-first birthday freed him from his articles of indenture.[7] George Bernard Shaw wrote that Gilbert, who had earlier adapted Offenbach's Les brigands, drew on that work also for his new libretto. Gilbert and Sullivan also inserted into Act II an idea they first considered for a one-act opera parody in 1876 about burglars meeting police, and their conflict escaping the notice of the father of a large family of girls. The composition of the music for Pirates was unusual, in that Sullivan wrote the music for the acts in reverse, intending to bring the completed Act II with him to New York, with Act I existing only in sketches. When he arrived in New York, however, he found that he had left the sketches behind, and he had to reconstruct the first act from memory. Gilbert told a correspondent many years later that Sullivan was unable to recall his setting of the entrance of the women's chorus, so they substituted the chorus "Climbing over rocky mountain" from their earlier opera, Thespis. Sullivan's manuscript for Pirates contains pages removed from a Thespis score, with the vocal parts altered from their original context as a four-part chorus. Some scholars (e.g. Tillett and Spencer, 2000) have offered evidence that Gilbert and Sullivan had planned all along to re-use "Climbing over rocky mountain," and perhaps other parts of Thespis, noting that the presence of the unpublished Thespis score in New York, when there were no plans to revive it, might not have been accidental. On 10 December 1879, Sullivan wrote a letter to his mother about the new opera, upon which he was hard at work in New York. "I think it will be a great success, for it is exquisitely funny, and the music is strikingly tuneful and catching." The work's title is a multi-layered joke. On the one hand, Penzance was a docile seaside resort in 1879, and not the place where one would expect to encounter pirates. On the other hand, the title was also a jab at the theatrical pirates who had staged unlicensed productions of H.M.S. Pinafore in America. To secure British copyright, a D'Oyly Carte touring company gave a perfunctory performance of Pirates the afternoon before the New York premiere, at the Royal Bijou Theatre in Paignton, Devon, organised by Helen Lenoir (who would later marry Richard D'Oyly Carte). The cast, which was performing Pinafore in the evenings in Torquay, travelled to nearby Paignton for the matinee, where they read their parts from scripts carried onto the stage, making do with whatever costumes they had on hand. Production and aftermath Pirates opened on 31 December 1879 in New York and was an immediate hit. On 2 January 1880, Sullivan wrote, in another letter to his mother from New York, "The libretto is ingenious, clever, wonderfully funny in parts, and sometimes brilliant in dialogue – beautifully written for music, as is all Gilbert does. ... The music is infinitely superior in every way to the Pinafore – 'tunier' and more developed, of a higher class altogether. I think that in time it will be very popular." Sullivan's prediction was correct. After a strong run in New York and several American tours, Pirates opened in London on 3 April 1880, running for 363 performances there. It remains one of the most popular G&S works. The critics' notices were generally excellent in both New York and London. The character of Major-General Stanley was widely taken to be a caricature of the popular general Sir Garnet Wolseley. The biographer Michael Ainger, however, doubts that Gilbert intended a caricature of Wolseley, identifying instead General Henry Turner, uncle of Gilbert's wife, as the pattern for the "modern Major-General". Gilbert disliked Turner, who, unlike the progressive Wolseley, was of the old school of officers. Nevertheless, in the original London production, George Grossmith imitated Wolseley's mannerisms and appearance, particularly his large moustache, and the audience recognised the allusion. Wolseley himself, according to his biographer, took no offence at the caricature and sometimes sang "I am the very model of a modern Major-General" for the private amusement of his family and friends.

Résumé: Frederic, who, having completed his 21st year, is released from his apprenticeship to a band of tender-hearted pirates. He meets Mabel, the daughter of Major-General Stanley, and the two young people fall instantly in love. Frederic finds out, however, that he was born on 29 February, and so, technically, he only has a birthday each leap year. His apprenticeship indentures state that he remains apprenticed to the pirates until his 21st birthday, and so he must serve for another 63 years.[2] Bound by his own sense of duty, Frederic's only solace is that Mabel agrees to wait for him faithfully

Création: 31/12/1879 - Fifth Avenue Theatre (Broadway) - représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 2 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse

La sixième collaboration de Gilbert & Sullivan fut "Patience". Le spectacle a été créé le 23 avril 1881 à l'Opéra Comique et a tenu l'affiche 578 représentations avant un transfert le 10 octobre 1881 dans le nouveau théâtre de D'Oyly Carte, le Savoy, premier théâtre au monde entièrement éclairé par des lumières électriques. "Patience" fait la satire de l'engouement esthétique des années 1870 et 80, lorsque la production de poètes, compositeurs, peintres et designers de toutes sortes fut totalement prolifique - mais, selon certains, fut surtout creuse et complaisante. Ce mouvement artistique était si populaire, et aussi si facile à ridiculiser comme une mode sans signification, qu'il a fait de "Patience" un grand succès. Le lien avec cette actualité ponctuelle de l'histoire peut rendre "Patience" un peu moins accessible à certains publics modernes, et les fans de Gilbert & Sullivan ont tendance à avoir des sentiments excessivements tranchés - positifs ou négatifs - à propos de "Patience".

Genèse: The opera is a satire on the aesthetic movement of the 1870s and '80s in England, part of the 19th-century European movement that emphasised aesthetic values over moral or social themes in literature, fine art, the decorative arts, and interior design. Called "Art for Art's Sake", the movement valued its ideals of beauty above any pragmatic concerns. Although the output of poets, painters and designers was prolific, some argued that the movement's art, poetry and fashion was empty and self-indulgent. That the movement was so popular and also so easy to ridicule as a meaningless fad helped make Patience a big hit. The same factors made a hit out of The Colonel, a play by F. C. Burnand based partly on the satiric cartoons of George du Maurier in Punch magazine. The Colonel beat Patience to the stage by several weeks, but Patience outran Burnand's play. According to Burnand's 1904 memoir, Sullivan's friend the composer Frederic Clay leaked to Burnand the information that Gilbert and Sullivan were working on an "æsthetic subject", and so Burnand raced to produce The Colonel before Patience opened. Modern productions of Patience have sometimes updated the setting of the opera to an analogous era such as the hippie 1960s, making a flower-child poet the rival of a beat poet. The two poets in the opera are given to reciting their own verses aloud, principally to the admiring chorus of rapturous maidens. The style of poetry Bunthorne declaims strongly contrasts with Grosvenor's. The former's, emphatic and obscure, bears a marked resemblance to Swinburne's poetry in its structure, style and heavy use of alliteration. The latter's "idyllic" poetry, simpler and pastoral, echoes elements of Coventry Patmore and William Morris. Gilbert scholar Andrew Crowther comments, "Bunthorne was the creature of Gilbert's brain, not just a caricature of particular Aesthetes, but an original character in his own right." The makeup and costume adopted by the first Bunthorne, George Grossmith, used Swinburne's velvet jacket, the painter James McNeill Whistler's hairstyle and monocle, and knee-breeches like those worn by Oscar Wilde and others. According to Gilbert's biographer Edith Browne, the title character, Patience, was made up and costumed to resemble the subject of a Luke Fildes painting. Patience was not the first satire of the aesthetic movement played by Richard D'Oyly Carte's company at the Opera Comique. Grossmith himself had written a sketch in 1876 called Cups and Saucers that was revived as a companion piece to H.M.S. Pinafore in 1878, which was a satire of the blue pottery craze. A popular misconception holds that the central character of Bunthorne, a "Fleshly Poet," was intended to satirise Oscar Wilde, but this identification is retrospective. According to some authorities, Bunthorne is inspired partly by the poets Algernon Charles Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who were considerably more famous than Wilde in early 1881 before Wilde published his first volume of poetry. Rossetti had been attacked for immorality by Robert Buchanan (under the pseudonym "Thomas Maitland") in an article called "The Fleshly School of Poetry", published in The Contemporary Review for October 1871, a decade before Patience. Nonetheless, Wilde's biographer Richard Ellmann suggests that Wilde is a partial model for both Bunthorne and his rival Grosvenor. Carte, the producer of Patience, was also Wilde's booking manager in 1881 as the poet's popularity took off. In 1882, after the New York production of Patience opened, Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte sent Wilde on a US lecture tour, with his green carnation and knee-breeches, to explain the English aesthetic movement, intending to help popularise the show's American touring productions. Although a satire of the aesthetic movement is dated today, fads and hero-worship are evergreen, and "Gilbert’s pen was rarely sharper than when he invented Reginald Bunthorne". Gilbert originally conceived Patience as a tale of rivalry between two curates and of the doting ladies who attended upon them. The plot and even some of the dialogue were lifted straight out of Gilbert's Bab Ballad "The Rival Curates." While writing the libretto, however, Gilbert took note of the criticism he had received for his very mild satire of a clergyman in The Sorcerer, and looked about for an alternative pair of rivals. Some remnants of the Bab Ballad version do survive in the final text of Patience. Lady Jane advises Bunthorne to tell Grosvenor: "Your style is much too sanctified – your cut is too canonical!" Later, Grosvenor agrees to change his lifestyle by saying, "I do it on compulsion!" – the very words used by the Reverend Hopley Porter in the Bab Ballad. Gilbert's selection of aesthetic poet rivals proved to be a fertile subject for topsy-turvy treatment. He both mocks and joins in Buchanan's criticism of what the latter calls the poetic "affectations" of the "fleshly school" – their use of archaic terminology, archaic rhymes, the refrain, and especially their "habit of accenting the last syllable in words which in ordinary speech are accented on the penultimate." All of these poetic devices or "mediaevalism's affectations", as Bunthorne calls them, are parodied in Patience. For example, accenting the last syllable of "lily" and rhyming it with "die" parodies two of these devices at once. On 10 October 1881, during its original run, Patience transferred to the new Savoy Theatre, the first public building in the world lit entirely by electric light. Carte explained why he had introduced electric light: "The greatest drawbacks to the enjoyment of the theatrical performances are, undoubtedly, the foul air and heat which pervade all theatres. As everyone knows, each gas-burner consumes as much oxygen as many people, and causes great heat beside. The incandescent lamps consume no oxygen, and cause no perceptible heat." When the electrical system was ready for full operation, in December 1881, Carte stepped on stage to demonstrate the safety of the new technology by breaking a glowing lightbulb before the audience.

Résumé: Romancier, Billy Magee fait un pari avec son riche ami qu’il peut écrire un roman en 24 heures. On lui remet une clé de l’auberge Baldpate, et on lui dit que c’est la seule (il s’avère qu’il y a sept personnes différentes qui revendiquent la propriété de la prétendue clé unique). À l’auberge, il déjoue un complot concernant un groupe de criminels, et juste avant minuit, apprend que l’intrigue entière est un canular (inventée par son riche ami pour l’empêcher de terminer le roman).

Création: 23/4/1881 - Opera Comique (Londres) - 578 représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: W.S. Gilbert • Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 5 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

"Iolanthe" a ouvert au Savoy Theatre le 25 novembre 1882, trois soirs après la dernière représentation de "Patience" au même théâtre et est resté à l'affiche pour 398 représentations. Gilbert avait déjà fait des coups de feu à l’aristocratie, mais dans ce "opéra de fées", la Chambre des Lords est ridiculisée comme un bastion de l’inefficace, privilégié et débile. Le système des partis politiques et d’autres institutions viennent aussi pour une dose de satire. Pourtant, à la fois auteur et compositeur a réussi à coucher la critique parmi ces rebondissements, aimables absurdités que tout est reçu comme bon amusement. Gilbert et Sullivan étaient tous deux à l’apogée de leur créativité en 1882, et beaucoup de gens estiment qu’Iolanthe, leur septième collaboration, est la plus parfaite de leurs collaborations.

Genèse: The opening night of Iolanthe was an occasion for what must have seemed a truly magical event in 1882. The Savoy Theatre was the first theatre in the world to be wired for electricity, and such stunning special effects as sparkling fairy wands were possible. Gilbert had targeted the aristocracy for satiric treatment before, but in this "fairy opera", the House of Lords is lampooned as a bastion of the ineffective, privileged and dim-witted. The political party system and other institutions also come in for a dose of satire. Among many potshots that Gilbert takes at lawyers in this opera, the Lord Chancellor sings that he will "work on a new and original plan" that the rule (which holds true in other professions, such as the military, the church and even the stage) that diligence, honesty, honour, and merit should lead to promotion "might apply to the bar". Throughout Iolanthe, however, both author and composer managed to couch the criticism among such bouncy, amiable absurdities that it is all received as good humour. In fact, Gilbert later refused to allow quotes from the piece to be used as part of the campaign to diminish the powers of the House of Lords. Although titled Iolanthe all along in Gilbert's plot book, for a time the piece was advertised as Perola and rehearsed under that name. According to an often-repeated fiction, Gilbert and Sullivan did not change the name to Iolanthe until just before the première. In fact, the title was advertised as Iolanthe as early as 13 November 1882 – eleven days before the opening – so the cast had at least that much time to learn the name. It is also clear that Sullivan's musical setting was written to match the cadence of the word "Iolanthe," and could only accommodate the word "Perola" by preceding it (awkwardly) with "O", "Come" or "Ah". A glittering crowd attended the first night in London, including Captain (later Captain Sir) Eyre Massey Shaw, head of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade, whom the Fairy Queen apostrophizes in the second act ("Oh, Captain Shaw/Type of true love kept under/Could thy brigade with cold cascade/Quench my great love, I wonder?"). On the first night, Alice Barnett as the Fairy Queen sang the verses directly to the Captain, to the great delight of the audience.

Résumé: L'intrigue se centre sur le personnage d'Iolanthe, une fée qui a été bannie du pays des fées parce qu'elle se marie avec un homme mortel, ce qui est interdit par la loi des fées. Son fils, Stréphon, est un pasteur arcadien qui veut se marier avec Phyllis, une pupille de la cour de la Chancellerie (Court of Chancery). Tous les membres de la chambre des Lords (House of Peers) veulent aussi se marier avec Phyllis. Quand Phyllis voit Strephon embrassant une jeune femme (ne sachant pas que c'est sa mère), elle se met en colère et crée une confrontation entre les pairs et les fées. La pièce satirise beaucoup des aspects du gouvernement, de la loi et de la société de Grande-Bretagne.

Création: 25/11/1882 - Savoy Theatre (Londres) - représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: W.S. Gilbert • Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 2 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

La huitième collaboration de Gilbert et Sullivan, "Princess Ida", ouvrit ses portes le 5 janvier 1884 au Savoy Theatre pour 246 représentations. Pour créer le livret, Gilbert s'est tourné vers une pièce qu’il avait écrite en 1870, intitulée "The Princess", et réutilisa une grande partie du dialogue de cette pièce. Il conserva sa structure en trois actes, mais il écrivit de nouvelles paroles pour Sullivan. Sullivan fournit une partie de la meilleure musique qu’il ait jamais écrite pour le Savoy. La pièce et l’opéra s’inspirent des personnages et des incidents du poème narratif en vers vierges de Tennyson, The Princess, publié en 1847.

Genèse:

Génèse

Princess Ida is based on Tennyson's serio-comic narrative poem of 1847, The Princess: A Medley. Gilbert had written a blank verse musical farce burlesquing the same material in 1870 called The Princess. He reused a good deal of the dialogue from this earlier play in the libretto of Princess Ida. He also retained Tennyson's blank verse style and the basic story line about a heroic princess who runs a women's college and the prince who loves her. He and his two friends infiltrate the college disguised as female students. Gilbert wrote entirely new lyrics for Princess Ida, since the lyrics to his 1870 farce were written to previously existing music by Offenbach, Rossini and others. Tennyson's poem was written, in part, in response to the founding of Queen's College, London, the first college of women's higher education, in 1847. When Gilbert wrote The Princess in 1870, women's higher education was still an innovative, even radical concept. Girton College, one of the constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge, was established in 1869. However, by the time Gilbert and Sullivan collaborated on Princess Ida in 1883, a women's college was a more established concept. Westfield College, the first college to open with the aim of educating women for University of London degrees, had opened in Hampstead in 1882. Thus, women's higher education was in the news in London, and Westfield is cited as a model for Gilbert's Castle Adamant. Increasingly viewing his work with Gilbert as unimportant, beneath his skills and repetitious, Sullivan had intended to resign from the partnership with Gilbert and Richard D'Oyly Carte after Iolanthe, but after a recent financial loss, he concluded that his financial needs required him to continue writing Savoy operas. Therefore, in February 1883, with Iolanthe still playing strongly at the Savoy Theatre, Gilbert and Sullivan signed a new five-year partnership agreement to create new operas for Carte upon six months' notice. He also gave his consent to Gilbert to continue with the adaptation of The Princess as the basis for their next opera. Later that spring, Sullivan was knighted by Queen Victoria and the honour was announced in May at the opening of the Royal College of Music. Although it was the operas with Gilbert that had earned him the broadest fame, the honour was conferred for his services to serious music. The musical establishment, and many critics, believed that Sullivan's knighthood should put an end to his career as a composer of comic opera – that a musical knight should not stoop below oratorio or grand opera. Having just signed the five-year agreement, Sullivan suddenly felt trapped. By the end of July 1883, Gilbert and Sullivan were revising drafts of the libretto for Ida.[9] Sullivan finished some of the composition by early September when he had to begin preparations for his conducting duties at the triennial Leeds Festival, held in October. In late October, Sullivan turned his attentions back to Ida, and rehearsals began in November. Gilbert was also producing his one-act drama, Comedy and Tragedy, and keeping an eye on a revival of his Pygmalion and Galatea at the Lyceum Theatre by Mary Anderson's company. In mid-December, Sullivan bade farewell to his sister-in-law Charlotte, the widow of his brother Fred, who departed with her young family to America, never to return. Sullivan's oldest nephew, Herbert, stayed behind in England as his uncle's ward, and Sullivan threw himself into the task of orchestrating the score of Princess Ida. As he had done with Iolanthe, Sullivan wrote the overture himself, rather than assigning it to an assistant as he did in the case of most of his operas.Production

Princess Ida is the only Gilbert and Sullivan work with dialogue entirely in blank verse and the only one of their works in three acts (and the longest opera to that date). The piece calls for a larger cast, and the soprano title role requires a more dramatic voice than the earlier works. The American star Lillian Russell was engaged to create the title role of Princess Ida, but Gilbert did not believe that she was dedicated enough, and when she missed a rehearsal, she was dismissed. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company's usual female lead, Leonora Braham, a light lyric soprano, nevertheless moved up from the part of Lady Psyche to assume the title role. Rosina Brandram got her big break when Alice Barnett became ill and left the company for a time, taking the role of Lady Blanche and becoming the company's principal contralto. The previous Savoy opera, Iolanthe, closed after 398 performances on 1 January 1884, the same day that Sullivan composed the last of the musical numbers for Ida. Despite grueling rehearsals over the next few days, and suffering from exhaustion, Sullivan conducted the opening performance on 5 January 1884 and collapsed from exhaustion immediately afterwards. The reviewer for the Sunday Times wrote that the score of Ida was "the best in every way that Sir Arthur Sullivan has produced, apart from his serious works.... Humour is almost as strong a point with Sir Arthur... as with his clever collaborator...." The humour of the piece also drew the comment that Gilbert and Sullivan's work "has the great merit of putting everyone in a good temper." The praise for Sullivan's effort was unanimous, though Gilbert's work received some mixed notices.Aftermath

Sullivan's close friend, composer Frederic Clay, had suffered a serious stroke in early December 1883 that ended his career. Sullivan, reflecting on this, his own precarious health and his desire to devote himself to more serious music, informed Richard D'Oyly Carte on 29 January 1884 that he had determined "not to write any more 'Savoy' pieces." Sullivan fled the London winter to convalesce in Monte Carlo as seven provincial tours (one with a 17-year-old Henry Lytton in the chorus) and the U.S. production of Ida set out. As Princess Ida began to show signs of flagging early on, Carte sent notice, on 22 March 1884, to both Gilbert and Sullivan under the five-year contract, that a new opera would be required in six months' time.[20] Sullivan replied that "it is impossible for me to do another piece of the character of those already written by Gilbert and myself." Gilbert was surprised to hear of Sullivan's hesitation and had started work on a new opera involving a plot in which people fell in love against their wills after taking a magic lozenge – a plot that Sullivan had previously rejected. Gilbert wrote to Sullivan asking him to reconsider, but the composer replied on 2 April that he had "come to the end of my tether" with the operas: “...I have been continually keeping down the music in order that not one [syllable] should be lost.... I should like to set a story of human interest & probability where the humorous words would come in a humorous (not serious) situation, & where, if the situation were a tender or dramatic one the words would be of similar character." Gilbert was much hurt, but Sullivan insisted that he could not set the "lozenge plot." In addition to the "improbability" of it, it was too similar to the plot of their 1877 opera, The Sorcerer, and was too complex a plot. Sullivan returned to London, and, as April wore on, Gilbert tried to rewrite his plot, but he could not satisfy Sullivan. The parties were at a stalemate, and Gilbert wrote, "And so ends a musical & literary association of seven years' standing – an association of exceptional reputation – an association unequalled in its monetary results, and hitherto undisturbed by a single jarring or discordant element." However, by 8 May 1884, Gilbert was ready to back down, writing, "...am I to understand that if I construct another plot in which no supernatural element occurs, you will undertake to set it? ... a consistent plot, free from anachronisms, constructed in perfect good faith & to the best of my ability." The stalemate was broken, and on 20 May, Gilbert sent Sullivan a sketch of the plot to The Mikado. A particularly hot summer in London did not help ticket sales for Princess Ida and forced Carte to close the theatre during the heat of August. The piece ran for a comparatively short 246 performances, and for the first time since 1877, the opera closed before the next Savoy opera was ready to open. Princess Ida was not revived in London until 1919. Some of these events are dramatised in the 1999 film Topsy-Turvy.Résumé: La pièce raconte l'histoire d'une princesse qui fonde une université pour femmes qui enseigne que les femmes sont supérieures aux hommes et qu'elles devraient diriger. Le prince avec lequel elle a été mariée de force entre avec deux de ses amis dans l'université en se déguisant en femmes. Ils sont découverts, et une véritable guerre entre les deux sexes se prépare.

Création: 5/1/1884 - Savoy Theatre (Londres) - 246 représ.

Musical

Musique: Arthur Sullivan • Paroles: W.S. Gilbert • Livret: W.S. Gilbert • Production originale: 9 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Génèse Liste chansons

"The Mikado" est la neuvième des quatorze collaborations de Gilbert et Sullivan et est l'une des plus jouées du duo avec "The Pirates of Penzance" et "H.M.S. Pinafore". La première représentation eut lieu le 14 mars 1885, à Londres, et se joua au Savoy Theatre pendant 672 représentations ce qui à l'époque, est la deuxième plus longue série de représentations d'une œuvre théâtrale musicale, et l'une des plus longues séries pour une œuvre théâtrale en général. Certains airs de cet opéra comme "Three Little Maids from School" ou "I've Got a Little List" demeurent extrêmement populaires de nos jours dans la culture anglo-saxonne et ont connu de nombreuses adaptations et parodies.

Genèse:

Origines