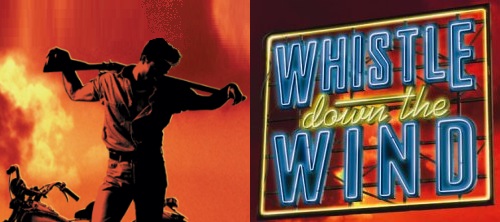

I joined Andrew and Jim on Whistle Down the Wind for its first airing at the Sydmonton Festival in 1995 when it was thought to be a musical film, adapted by Pat Knop from the original classic and already transported from rural Yorkshire to a new life in America’s Deep South.

During the Sydmonton workshop we had the challenge of putting what was then thought to be a screenplay onto the stage and so the first metamorphosis began. It was immediately apparent that the powerful and moving effect it had in live performance left no doubt that this was, first and foremost, a musical for the theatre.

The 1950s was the era at the heart of the American dream. Film and advertising sought to represent the fierce sense of American pride born out of the need to numb the dark years of Depression and war. Communities settled in new areas with heartfelt optimism, only to discover that the reality fell far short of their expectations. Poverty and deep dissatisfaction with life became a catalyst for social and racial tension and is the source of the longing in the hearts of all the major characters.

The set design was inspired by these things and by a trip with Peter Davison around the Louisiana countryside; a rural landscape blighted in the post war period by the arrival of oil refineries and concrete freeways carving across it from one metropolis to another, turning small towns into forgotten backwaters. The freeway became the metaphor for the design; the route of escape that hangs tantalizingly over the characters’ heads beckoning them into motion. It is also a powerful image for the spiritual journey along an ambiguous road which floats between heaven and earth.

Swallow dreams of the return of her mother and the emotional comfort and security she would bring. Candy has invented the myth for herself that paradise lies at the end of the freeway. Amos wants to escape the fate of his father working in the oil refinery. Boone dreams of a better life for his motherless kids. The desire for change is uppermost in all their minds yet all are ‘stuck’ by circumstance or by their own personalities in a helpless inertia.

The Man who appears out of nowhere in Swallow’s barn and finally disappears as dramatically and enigmatically as he arrived is both real and a kind of mythological figure who becomes the catalyst for change in the whole community. Only Swallow and the local kids actually see him face to face, yet he becomes a powerful force for transformation in everyone around him.

Swallow’s transformation from girl to woman leaves her emotions skidding out of control as she wrestles with her perceptions of desire and love. Her initial faith – innocent and blinding – slowly gives way to a more adult kind of love based on knowledge and forgiveness.

Just as the woman is awakened in Swallow, she in turn awakens the goodness within the dark heart of the unredeemable convict. They have the power to save each other but her innocence and his guilt are too far removed to be resolved without pain. Just as in every good fairy story, there lurk dark and dangerous truths; scratch the surface and you reveal a troubled world of secrets and denial. Cruelty and tenderness live side by side in ever exhausting conflict. The deep void between the adult world and the children’s world is one of the major thematic tensions in the piece, raising questions of lost innocence and the tyranny of fear.

This is a story about true love among real people but the issues and resonances of the piece have always felt epic and universal rather than simply domestic or trivial. This production attempts to explore some of those themes which run repeatedly through classical and archetypal stories. Open your hearts and let the winds of change carry you into the unknown.

Gale Edwards , from the programme for the original London production

.png)

.png)