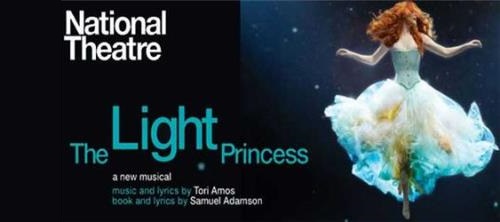

Tori Amos's musical The Light Princess has been five years in the making but now it’s about to be unveiled at the National Theatre.

Expect original songs, magical puppetry and a woman floating above the stage.

Fairy-tale twist: red-headed Rosalie Craig, left - who bears more than a passing resemblance to composer and co-lyricist Tori Amos, right - plays the Light Princess.

Fairy-tale twist: red-headed Rosalie Craig, left - who bears more than a passing resemblance to composer and co-lyricist Tori Amos, right - plays the Light Princess.

"Nick Hytner told me, 'Writing a musical is a glorious nightmare'," Tori Amos tells me frankly. "He said, 'You will have the ride of your life. But you will have to be willing to tear the structure down and write it again'."

It clearly has been a ride. Amos’s musical, The Light Princess, was originally due in 2011 and yet only reaches the National Theatre’s Lyttelton stage at the end of this month.

The omens are good: it comes with award-winning director Marianne Elliott attached, whose track record includes War Horse.

It is, despite such stellar support, a very personal project for Amos, 49, who has written the music and lyrics, with playwright Samuel Adamson (Pillars of the Community, Breakfast at Tiffany’s) contributing the book. Not only has The Light Princess occupied her for the past five years but the subject matter — female sexual awakening — is close to her heart. Which is why Amos, from North Carolina but who now divides her time between Florida, Ireland and Cornwall, has spent the summer in a Southwark rehearsal room.

Loosely adapted from George MacDonald’s 19th-century fairy tale, The Light Princess tells the story of Althea, a princess living under a curse who becomes light with grief and has to be locked up to stop her floating away. Only when she has mastered the art of crying can she be grounded and marry the prince who has fallen in love with her.

It’s rich psychological material for Amos, who has documented her own religious upbringing, sexual relationships, miscarriages and pregnancy in taboo-breaking songs such as Cornflake Girl, Professional Widow and God. As a survivor of sexual violence at 21, she co-founded Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), an anti-sexual assault organisation working with local crisis centres across the US.

Although drawn to the fairy tale elements of MacDonald’s story, she insists, “We had no desire to set it before the birth of women’s rights. We wanted a teenage lead who could resonate with 21st-century teens and their parents.”

Amos is sworn to secrecy about how Althea will actually float around the stage but, like War Horse, the show will feature animation, puppetry and aerial effects. There will also be a live orchestra but the production won’t be full of show-stopping numbers. Song, dialogue and movement are integrated. “Sam and I made a choice to keep a dramatic through-line through the song, so we don’t stop a show to just bask in emotion.”

Amos has sold more than 12 million albums and been Grammy-nominated eight times. She first burst onto the music scene in 1992 with her solo album, Little Earthquakes, a set of piano-based songs. She confirmed her status as one of pop’s most imaginative female artists with subsequent albums including Under the Pink, Boys for Pele and the covers set, Strange Little Girls. Most recently she has recorded two albums on the classical label Deutsche Grammophon. But she’s never written a musical before.

Initially Amos approached Broadway promoters with the concept for The Light Princess but realised that she needed a creative producer, “not just one looking at the dollar signs”. She was advised to meet Hytner, the National Theatre’s artistic director, “because they were looking for contemporary musicians to work with”.

Even though he spelled out the difficulties of writing a great musical (“there’s a graveyard full of them”), Amos knew she had met the right producer. “I like a dangerous pit,” she says with a gleam.

The National arranged for her to meet Adamson (who also adapted the film All About My Mother for the Old Vic) and a creative partnership bloomed. Today she calls him her “paper husband”. Originally only she wrote the songs but now they’re writing them together. “We’re relentless with each other. I’ll look at him and say, ‘If it’s better in dialogue, just take it’.”

The relationship was tested when Hytner postponed the opening. “It was the right decision,” Amos says now. “Nick said to me, ‘This musical has to be better than good. I’m not asking you to go away and dumb this down, or make it for every demographic so we can cash in. I’m telling you the opposite. Go darker, be brave. You can say things to teenagers and adults that will resonate with them when they leave the theatre, things they might have been arguing about that week’.”

She and Adamson went away to re-write. Two years later, it’s ready. Elliott has brought in a crack team including designer Rae Smith (who won the Evening Standard Best Design Award for War Horse), music supervisor Martin Lowe and choreographer Steven Hoggett (Black Watch, Once).

It’s like a masterclass in theatre every day, Amos enthuses.

“Marianne is at the top of her game right now. This is her first musical and the rigour she puts on her whole creative team, I haven't seen anything like it in my life. She empowers us all to go off and create with each other, and then we come back and she oversees everything.”

Amos relishes being hands-on. “Sometimes you’re having to compose on the spot because the visual team needs another 20 bars because a new scene has been added. And I don’t believe in filler. Sonic design is an aphrodisiac when you get it right.”

The cast for Light Princess is a combination of performers from musical theatre (Clive Rowe, Hal Fowler) and straight actors. Red-headed Rosalie Craig (who resembles a young Amos) plays Althea. “She has been training for 18 months to play the role,” Amos says. Nick Hendrix (last seen in The Winslow Boy) is warrior prince Digby.

Amos, who calls her songs her “girls”, has never composed for men before and has loved writing for Rowe’s extraordinary vocal range (he plays the Light Princess’s father). “It’s almost a three-octave range, which is very rare both sides of the Atlantic.”

Even when the actors break for lunch, she bolts back to the rehearsal room so that she can listen to the creative team. She and Craig joke they’d like to stay there in sleeping bags. Many pop singers would be at sea in a National Theatre rehearsal room but Amos credits her parents’ insistence on a rounded music education for their daughter. Classically trained, she attended the Peabody Conservatory of Music at the age of 11.

“My mother was a vicar’s wife in the Sixties before the feminist movement so she plied a lot of her vision into me. When my father went to work, out would come her record collection and she would play me everything from Fats Waller and Billie Holiday to musical theatre.”

In 2011 she recorded Night of Hunters, featuring tributes to Bach, Chopin and Schubert, followed by Gold Dust (2012) which saw her reworking her early songs with the Metropole Orchestra.

It opened her up to “endless reams of classical music that I hadn’t looked at for years or never been open to. I love Schubert but I hadn’t listened to Winterreise before. And that was all happening during the rewrites of The Light Princess.”

The piece is about grief — Althea and her prince have both lost their mothers, and need to learn to separate from the powerful fathers. It’s made her question her own role as a parent. “We do things to children; we don’t always handle things well.”

She and her husband, English sound engineer Mark Hawley, have a daughter (“13 going on 32”) and her sister has five children. So The Light Princess is shot through with raw teenage life.

In many ways, Amos doesn’t envy modern childhood. “We think it’s easier because they have exposure and social networking but you can be globally embarrassed, not just at high school.”

Next she starts recording a new album for Universal. “But working with the National has changed me for ever. When I go back to my own world, I’m taking so much that I’ve learned with me.”

From London Evening Standard - Liz Hoggard - 28 août 2013

.png)

.png)